Centenary now

Modernism, James Michener and the crisis of the endless 1970s

1. The Commission

Only another Substacker, someone who had poured their heart out into a good post that got five hundred pageviews, could appreciate the thrill of receiving an email inviting me to a video chat with CEO Chris Best.

“You wrote that blog about Yellowstone, didn’t you?” said Best eagerly once we were on the call. “And the one about, what was it, El Dorado or rock painting or something? You haven’t posted in a while. What gives?”

“Well, I guess I just haven’t found the time,” I said hesitantly. “And I think my posts are a little more complicated than —”

“Yeah, yeah — have you ever considered writing about the suffocating illiberal orthodoxies of the successor ideology?” Best asked questioningly. “Or how a minor personnel dispute at a small liberal arts college in New England makes it okay to become a fascist? Or how cancel culture has made everyone afraid to even just ask questions about vaccine safety?” He paused, and a grave look came over his face. “Wait, Chase — have you stopped posting because you’ve been silenced by the woke mob?”

“I think I’m just looking for the right idea,” I replied. “I still want to do a big long thing on Edward Abbey, or maybe Ivan Doig. And I’m interested in interrogating the whole concept of the post-Western, some people call it the anti-Western, or the revisionist Western —”

“Listen, we probably need to hurry to the section break before people stop reading,” Best said quickly. “What do you think about a post on Centennial?”

“By God!” I yelled shoutily. “The thousand-page airport novel? The middlebrow doorstop they made into an unwatchable 20-hour miniseries? No one’s ever actually read that, have they? Not reading it is the point. It’s like Infinite Jest for high school gym teachers.”

“We can pay you nothing,” Best said.

“I’ll start today,” I replied.

2. The Author

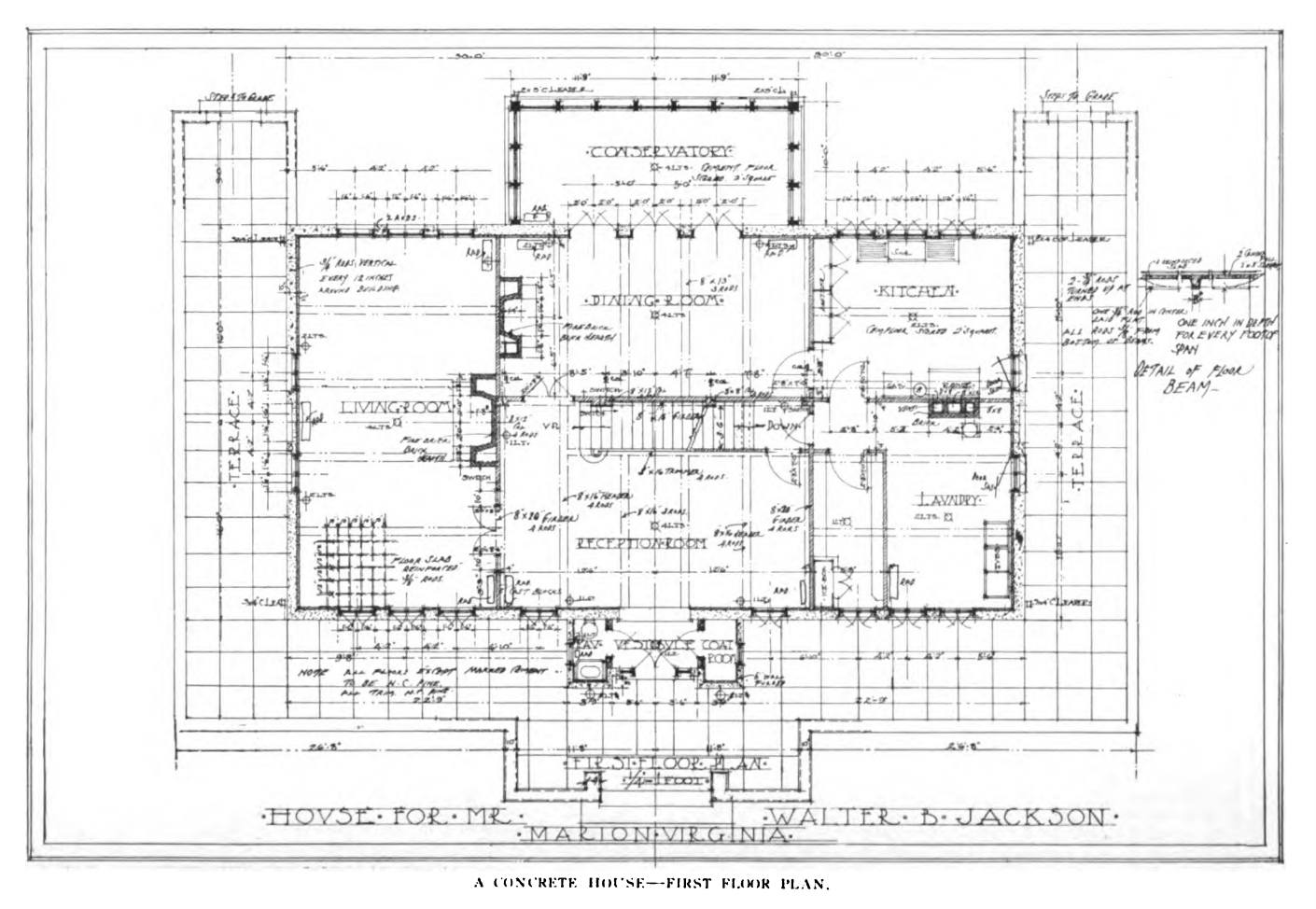

On a warm Friday night in Doylestown, Pennsylvania in June 1910, a company of firemen raced towards the north side of town, where there were reports of a barn on fire. Only when they’d arrived and run out their hoses did the firefighters discover, in the words of the Doylestown Daily Intelligencer, that “the alarm was a fake”; the blaze was in fact a bonfire that industrialist Henry Chapman Mercer “had made on top of his concrete mansion,” a 44-room structure known to locals as Fonthill Castle. For Mercer, the fire was at once a birthday celebration and a thumbing of his nose at all those around town who’d disdained his use of what was then a newfangled construction method, in which concrete was poured into place and reinforced with iron bars. The journal Cement Age, which had already profiled Mercer and his castle the year before, declared it “the sort of story that is causing the insurance man to sit up and take notice, and likewise the citizen who wants an indestructible house.”

Among the Doylestown mothers who struggled in those years to keep their children from adventuring into the sites where Mercer built Fonthill and other reinforced-concrete landmarks was one Mabel Michener, whose son James was known for tramping about and bothering townsfolk at the courthouse or the train station. “Most people in the borough thought Mercer was a fool,” writes Michener biographer John Hayes. “No one could erect a building without a hammer and nails and expect it to stand, they claimed … Parents warned their children to stay away from the site and, for that matter, from Mercer, too.” Young James didn’t listen, and even as a child “could explain in detail how they had been constructed,” adds Hayes. “Once or twice he even managed to strike up a conversation with Mercer.”

The two would’ve made an odd pair: the wealthy, Harvard-educated eccentric who rode around town on his bicycle and the nearly destitute Michener boy, whose dubious paternity kept his widowed mother on the fringes of Doylestown society. Mabel scrounged for work as a laundress and later opened a boardinghouse for orphaned children; though James claimed for much of his life to have been one of those orphans, accounts unearthed by Hayes indicate that Mabel gave birth to him in New York in 1907, five years after the death of her husband Edwin and ten years before taking in her first foster child.

A scholarship to Swarthmore College became Michener’s ticket out of poverty and into a stable middle-class career in education, taking him from Pennsylvania prep school classrooms to instruction at the Colorado State Teachers College in Greeley and ultimately to an editorship at the Macmillan Publishing Company’s textbook division in New York City. When the U.S. entered World War II, he sought a commission as a naval officer, and though the 37-year-old Lieutenant Michener’s tour of the Pacific as a supply clerk was effectively little more than an extended tropical vacation, it provided him with the material he needed for a long-planned leap into fiction writing.

Tales of the South Pacific was published in 1947, awarded a flukish and instantly controversial Pulitzer Prize the next year and adapted into a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical the year after that. The book’s unexpected success set Michener up for both a lifelong professional and financial security and a lifelong anxiety about his critical reputation and literary worthiness. In its wake, he spent a decade as what Hayes calls “the sole literary proprietor of the vast territory west of San Francisco,” penning short “Asiatic” novels in the vein of South Pacific.

Then, at age 50, Michener suddenly ditched Hemingwayesque understatement for the maximalist formula that would define the long latter half of his life and career. The 937-page Hawaii was the product of more than three years of intensive research and consultation with academics across a multitude of disciplines; Michener wrote and rewrote the 500,000-word manuscript from start to finish at least four times. Published three months after Hawaii became the 50th state, Hawaii quickly topped the bestseller lists, and the Michenerian epic was born.

In his sweeping The Dream of the Great American Novel, Harvard literary scholar Lawrence Buell describes the latest and most self-conscious category of attempts at the G.A.N. (as Henry James archly initialized it as early as 1880) as

compendious meganovels that assemble heterogeneous cross-sections of characters imagined as social microcosms or vanguards. These are networked loosely or tightly as they case may be, and portrayed as acting and interacting in relation to epoch-defining public events or crises, in such a way as to constitute an image of “democratic” promise or dysfunction.

Michener later named “family histories” like Glenway Wescott’s The Grandmothers and Eleanor Dark’s The Timeless Land as his chief influences in this new mode, but Hawaii and all his subsequent meganovels bear an obvious conceptual and titular resemblance to John Dos Passos’ U.S.A. trilogy, regarded for a time as an American Ulysses, the nation’s totemic achievement in modernist literature. In 1947, the same year that South Pacific had been received so indifferently by critics, a deluxe U.S.A. reissue prompted the New York Times Book Review to declare it “not only the longest but also the most important and the best of the many American novels written in the naturalistic tradition,” placing Dos Passos atop a list that included John Steinbeck, Sinclair Lewis and other giants of early 20th-century fiction.

Late in life, Dos Passos would tell the Paris Review that he had “always been a frustrated architect,” and as he was finishing the U.S.A. trilogy in the mid-1930s he penned an influential essay titled “The Writer as Technician.” Drawing explicit parallels between writing and scientific discovery, he argued that the mission of the writer should be to “discover the deep currents of historical change under the surface of opinions, orthodoxies, heresies, gossip and the journalistic garbage of the day,” endeavoring always to “probe deeper and deeper into men and events as you find them.”

With Hawaii, writes Hayes, Michener was satisfied that he’d proved himself as a “serious” writer, rather than just a “popular” one. Certainly no one could accuse the book of lacking a deep probing of history. His process was not unlike Henry Mercer’s: casting thick, solid layers of character and drama upon a sturdy frame of fact and scholarship, aiming to erect towering artistic edifices that could entertain and educate all at once — and stand the test of time. At the height of their ambition in the mid-20th century, the architectural modernists believed they could use the newest materials and the latest ways of thinking to build a better world from the ground up, and so it was with Michener.

So earnest was this belief, in fact, that his next major project after Hawaii was not a novel at all, but a hopeless run for Congress as a Democrat in his heavily Republican home district in Pennsylvania. Though he lost that race by 10 points, later in the 1960s he won a consolation of sorts in his election to a convention called to amend and modernize Pennsylvania’s state constitution. He seemed to enjoy this kind of thankless blue-ribbon committee work, and went on to accept appointments by President Richard Nixon to the advisory board of the U.S. Information Agency and, pivotally, the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission, tasked years in advance with developing a plan for the 1976 celebration.

An inveterate traveler, Michener had in the intervening years repeated the Hawaii formula with the 909-page The Source, set in Israel-Palestine, and the 818-page, nonfictional Iberia. But now he set his sights on something many of his most loyal fans, in their letters to him, had long clamored for: a meganovel set on the U.S. mainland, an epic that to his readers was more authentically American. His agent suggested California as the natural subject for such a book, while his longtime editor proposed a continent-spanning America. (That would have been an unmistakably direct challenge to Dos Passos, who died the same year.) Instead, Michener began plotting out a narrative that he soon realized had been more than three decades in the making, dating back to his days teaching history in northern Colorado, to visions of “an imaginary plains town … which has lived with me since 1937 when I first saw the Platte.”

Michener was an idealist deeply troubled by the bitter political tensions and civil unrest that plagued the country in the late 1960s, and through both the Bicentennial Commission and the novel that it inspired, he hoped to author what he called “a new spiritual agreement” among his fellow countrymen. Approaching his 64th birthday, he hinted to colleagues that it could well be his final book, and by the time he road-tripped to Colorado in late 1970 to begin another period of exhaustive research, Michener and his inner circle had wholly bought into the notion that Centennial would be his magnum opus, a career valedictory, his parting gift to America.

3. The Setting

Charles W. Caryl had already lived several versions of the American Dream before he settled in Colorado in 1894: an inventor and entrepreneur who’d patented a successful commercial fire extinguisher; a financier who’d gone bust in the industrializing South; a moralizing antipoverty crusader in the slums of New York, Boston and Philadelphia. Within a few years of his arrival in Denver, Caryl had rebuilt his fortune in gold mining, and once again tried his hand at progressive social reform with the publication of his utopian novel and stage play, New Era, in 1897.

This delightfully deranged book — its full title is New Era: Presenting the Plans for the New Era Union to Help Develop and Utilize the Best Resources of This Country: Also to Employ the Best Skill There Is Available to Realize the Highest Degree of Prosperity That is Possible for All Who Will Help to Attain It: Based on Practical and Successful Business Methods — is Caryl’s humble attempt to solve all the problems of human civilization in a brisk 194 pages.

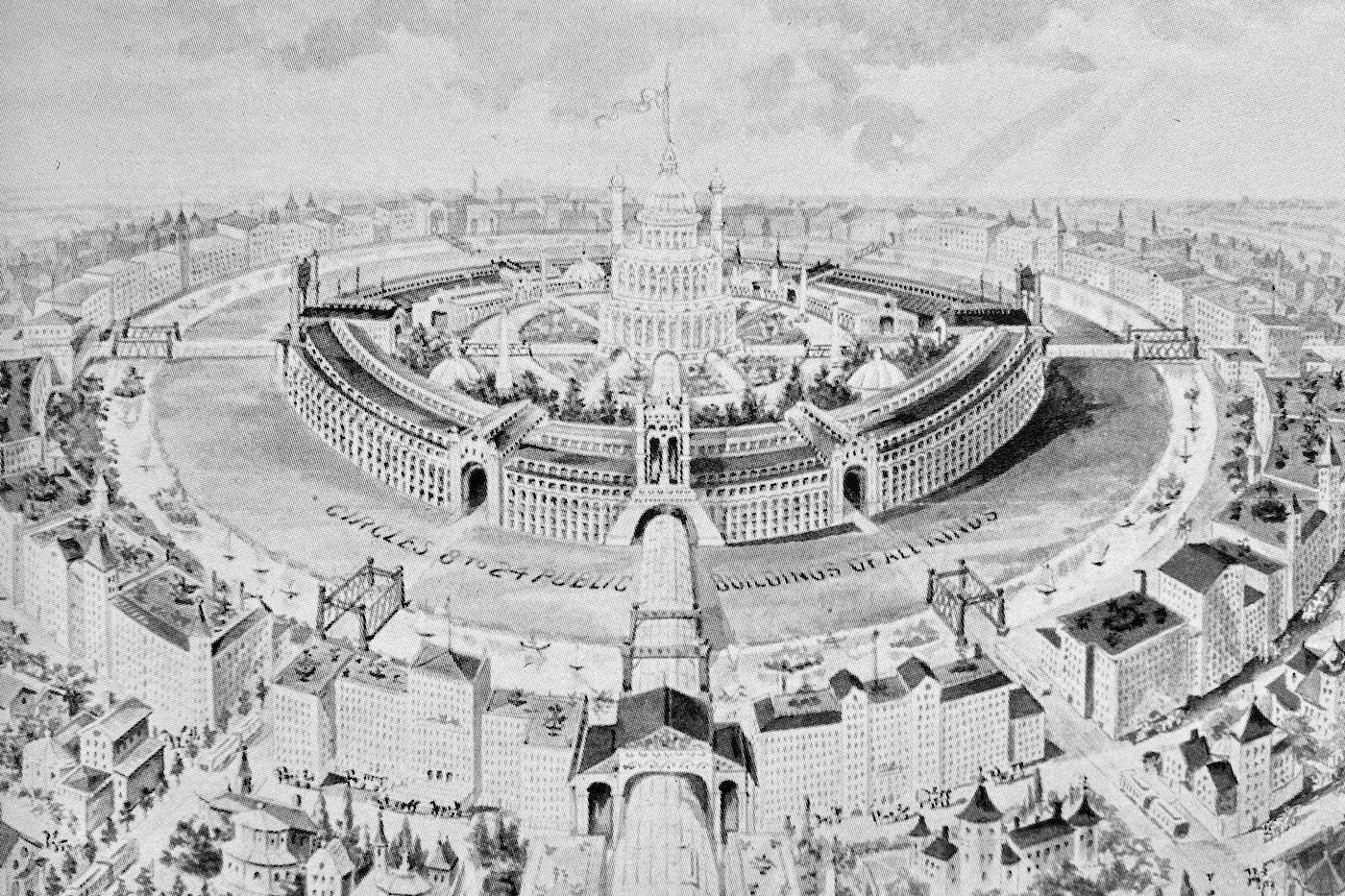

In a tone immediately familiar to those of us in the age of self-assured ultrarich dilettantes weighing in on the issues of the day on social media, Caryl confidently explained how financial panics, mass unemployment, deadly labor strife and all the other ills that plagued the Gilded Age would be brought to an end by his new, rationally designed paradise — a liberal technocrat’s vision of a world where, through the power of “all of the best inventions and improvements” furnished by modernity, wealth inequality was eased, but “there was no cause whatever for capitalists to fear their present investments would be impaired in any way.” In his fantasy, Caryl sketched out everything from a new system of government and fixed wage schedules to a minutely detailed street plan for the New Era Model City, home to a population of one to five million people, the building of which he predicted would be “by far the most stupendous and important enterprise ever accomplished on this planet by human beings.”

Colorado and its neighbors have long attracted dreamers and schemers like Charles Caryl. The conquered and depopulated lands of the West presented white settlers with a terra incognita upon which visionaries and zealots could imagine society rebuilt from the ground up. It was in the decades after the Centennial State’s founding, at the dawn of the modern age, that such utopianism was at its height across the world, uniting novelists and philosophers and reformers and bureaucrats in an exhilarating wave of optimism for the labor-saving mechanical production and bright electric lights of the future.

The mountain mining districts and empty grasslands of Colorado offered planners the rare opportunity to put their designs into action: Nathan Meeker’s Union Colony was the largest of a handful of such idealistic agrarian communities on the Eastern Plains, while farther west the town founded by the short-lived New Utopia Cooperative Land Association is today just called Nucla. An enduring utopian impulse can be detected in everything from New Deal resettlement proposals and the master-planned communities of the postwar period to present-day co-ops and off-the-grid communes. Coloradans may have adopted the primeval individualism of the Wild West as a kind of state ethos, but it’s arguably the search for a more enlightened, more advanced form of civilization, not the absence of it, that better describes Colorado’s past.

The utopian Union Colony, founded in 1869 and later incorporated as the city of Greeley, is the nearest geographical equivalent to Michener’s fictional Centennial, a mid-sized cow town situated at the confluence of the South Platte and Poudre rivers. Michener spent five years studying and teaching history in Greeley, no doubt becoming intimately familiar with its origins in agrarian utopianism, and yet his great saga of the West seems wholly uninterested in this enduring throughline of Western settlement; “the Greeley colony” is mentioned only a few times in passing, and the novel’s long list of stock characters includes plenty of frontiersmen, cowboys and homesteaders but no utopian dreamers, no communitarian idealists and no midcentury master planners.

The omission might not be worth noting at all were it not for the fact that Centennial is, at heart, just such an experiment in narrative form. In all its earnestness, its sprawling ambition, its faith in grand structures, there may be no purer expression of American literary modernism than this novel that announces itself in its opening chapter — a loopy framing device featuring a Michener stand-in and a fictional magazine assignment — as an attempt to capture “nothing less than the soul of America … as seen in microcosm.” Here is Michener, the intrepid novelist-historian, attempting a great act of authorial synthesis, drawing upon and fusing together the collected bodies of geological, climatological, biological and anthropological research into a coherent story spanning from the formation of the earth to the present.

Once the book’s main narrative gets going, the reader endures a hundred pages of descriptions of glacial erosion and bovine evolution before encountering a human story — and nothing is more essential to Centennial, or to the modernist project as a whole, than the conviction that a continuity of method should exist between the two. Through patient empirical observation and rational analysis, the modernist maintains, one can just as easily reveal objective truths about human beings and the optimal ways for their societies to be organized as a radiocarbon isotope can precisely date a mastodon fossil or a Clovis point.

The 20th century was to be the canvas on which modernism’s dream of a world made new could finally be realized. The “scientific management” of Frederick Winslow Taylor and the assembly line of Henry Ford, counterbalanced by the hard-won gains of progressive reformers and trade unionists, promised a new era of industrial prosperity in which the world’s working classes could finally share. In the laboratories and lecture halls of Europe, scientists on the bleeding edge of chemistry and physics, direct descendants of the great Enlightenment thinkers, inched closer to a unified theory of the fundamental building blocks of the universe. Visionaries like Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, the Swiss-French architect better known as Le Corbusier, drew up plans for buildings and city districts that reflected the efficiency and rationality of the machine age. “We claim,” wrote Jeanneret in 1923’s Towards a New Architecture, “in the name of the steamship, the airplane and the automobile, the right to health, logic, daring, harmony, perfection.”

Dos Passos probably still thought of himself as a political radical when he wrote “The Writer as Technician” in 1935, but the central point of his essay brims with this kind of ingenuous faith in the power of reason, in the perfectibility of human society and in the artist’s role in pursuing it. In a world being remade by technological advances and mass mechanization, even radicals could conceive of their political project as an earnest application of Enlightenment principles to persuade and inform the public of scientific truths:

The professional writer discovers some aspect of the world and invents out of the speech of his time some particularly apt and original way of putting it down on paper. If the product is compelling, and important enough, it molds and influences ways of thinking … The process is not very different from that of scientific discovery and invention. The importance of a writer, as of a scientist, depends upon his ability to influence subsequent thought. In his relation to society a professional writer is a technician just as much as an electrical engineer is.

The problem, of course, is that language is not a scientific instrument. An electrician can make a light bulb turn on because of certain undeniable physical properties of its wiring and the energy source that powers it; photons emitted by the light bulb reveal the material objects upon which it shines. Nothing of the sort can be said for acts of writing or speech. That an idea is “compelling” is no guarantee that it’s true, and if all that is required for a writer to be important is to “influence subsequent thought,” society can go to some very dark places indeed.

In 1898, Charles Caryl attempted to bring his New Era Union to fruition, establishing a colony of a few hundred people at one of his mining camps in the foothills of Boulder County. Little is known about how the experiment fared, beyond the fact that it fizzled within a year. Its failure seems to have sent Caryl on a manic downward spiral in search of increasingly far-fetched ways of realizing his utopian vision: from membership in a cult known as the Brotherhood of Light, which established a series of orphanages that were shut down by the state of Colorado following the deaths of at least nine young children; to claims made ahead of the 1904 World’s Fair that he had invented a “sun-ray” machine that would “soon replace steam and electricity”; to a newfound belief in the magical powers of a secret life-force called “vril,” which he turned out to have plagiarized from a different utopian novelist; and finally to the founding of another colony in California, where he was eventually caught seducing a number of “spiritual mates” with whom he wished to father a new race of “perfect human beings.” For Caryl and his followers, these ideas seem to have been plenty compelling.

Debate continues to this day over which of these strains of intellectual and political thought were ultimately spliced together into the forces responsible for the 20th century’s greatest madnesses and horrors. The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, who lived under both Nazi and Stalinist occupation before emigrating to the West in 1951, summed up one view: “Innumerable millions of human beings were killed in this century in the name of utopia.” And yet in the postwar decades, many people retained a faith in new, modern ways of thinking to build a world that was, if not Utopia, at least a better one than before.

Le Corbusier did things with concrete that Henry Mercer could only dream of, and his sketchbooks for La Ville Radieuse, a grand utopian city plan, would have made Charles Caryl blush. Though tainted by his brief association with the Vichy regime, Le Corbusier emerged as the architectural world’s leading postwar visionary, influencing a generation of urban planners with his proto-Brutalist model housing development, the Unité d'habitation. Each iteration of the dense, modular Unité promised ample residential, recreational and commercial space for its 1,600 inhabitants, a scaled-down realization of the Ville Radieuse vision. The first was completed in Marseilles in 1952, and before long Le Corbusier’s principles could be seen at work in modernist housing projects all over the world: Cabrini-Green, La Vele di Scampia, Heygate, Pruitt-Igoe.

One need not know the ultimate fate of each of these projects, or share Miłosz’s view of the dangers of utopian thought, to grasp some of problems inherent in modernism, whether they manifest in art or architecture or literature or political theory. It’s one thing to dream up a new world, and another to actually build it out of the raw, entrenched materials of the old one. How do you design a city, or a city block, or even just a building, to meet all of its residents’ needs? How do you author a narrative grand enough to organize a society around? How do you tell the story of an entire state, an entire region, an entire country, in a single book?

4. The Novel

I.

Well, maybe you can’t.

That Centennial is a failure on its own terms is plain not just from its ill-advised self-promotion as “the soul of America … in microcosm,” but from the expectation that Michener set for the book soon after its publication, when he predicted to a reporter that it would be read for hundreds of years, “because I told a story that needed to be told.” Just 25 years after Michener’s death, though, his work seems at risk of fading away completely.

At best, you’ll find present-day literary criticism listing Michener alongside other “diminished” midcentury writers like Bernard Malamud and Herman Wouk; at worst, he’s lumped in with the mass-market “drivel” of Tom Clancy and Danielle Steel. His epics are nowhere to be found on college syllabi, best-of lists or even in IP-hungry Hollywood pitch meetings. They may still be a bookstore staple, sure to be found on local-interest shelves in the Anchorage or Norfolk or Dallas airports, but for how much longer? The cover design copied across the latest paperback editions of Michener’s works gives some idea of how little the literary world now seems to know what to make of them, their low-saturation stock photos and faux-distressed textures marketing even the most panoramic of his works as something between a true-crime thriller and NCAA football memoir.

Michener could be forgiven, though, for feeling boastful in 1974, when Centennial smashed records to become the year’s best-selling work of fiction, even after Random House raised its hardcover price to an unprecedented $12.50. Certainly the publisher knew how to market the book at the time, its dust jacket of solid black and primary colors — an echo, deliberate or not, of the first complete edition of Dos Passos’ U.S.A. — and a literal Great Seal marking the enclosed 909 pages as a must-read national tome. Such was the interest in the book that Random House published two companion titles, About Centennial by Michener himself and In Search of Centennial by John Kings, a British-born Wyoming rancher who helped with the novel’s research and preparation. Adaptation rights were soon snatched up by Universal. It was in Centennial’s afterglow that Michener received his highest honor since South Pacific’s Pulitzer: President Gerald Ford awarded him the Medal of Freedom in 1977, crediting the “master storyteller” with having “expanded the knowledge and enriched the lives of millions.”

About a novel and a novelist that try so hard to be everything all at once, perhaps it serves to start with everything they definitively are not. In his biography, Hayes mounts a running defense of Michener that ends up conceding a great deal: his subject is “not a risk taker”; “neither stylist nor scholar”; “less thinker than craftsman”; “more social journalist than novelist.” Michener’s prose was “often stilted and awkward” and “not good writing,” much less “great literature,” Hayes adds. His work contained “no ambiguity, no irony, no paradox, no conceits,” wrote Pearl K. Bell in a 1981 Commentary piece. Even Michener himself, in the course of decades of agonizing over his critical reputation, arrived at a certain frankness about his own limitations. In Centennial’s frame story, his narrator and stand-in, historian Lewis Vernor, is advised by his editors “not to bother about literary style.” (“Evidently he takes them at their word,” quipped the New York Times’ review.) One year after Centennial’s publication, he told Hayes: “Character, dialogue, plot — all of that I leave to others.”

And so we have a thousand-page historical novel that excels neither as history nor as a novel, and offers little in the way of risk, style, technique, thought, character, dialogue or plot. Other than that, though, it can’t be denied that there’s a great deal to be found in Centennial: chiefly and most obviously, an immense amount of factual and near-factual material, rendered into long stretches of a shared national past portrayed more or less accurately, ordered into clauses and sentences and paragraphs that are almost entirely comprehensible, and — less obviously at first but in great bludgeoning blows over the reader’s head by the book’s end — plenty of didactic moralism about America’s place in and responsibility to the world.

Michener’s deep love of country was being tested like never before as he began to work on Centennial in earnest; his two previous books, the poorly received novel The Drifters and the nonfictional Kent State: What Happened and Why, both published in 1971, show him agonizing over the state of American society, and particularly the direction of its youth. Even the honor of a seat on Nixon’s Bicentennial Commission proved a bitter disappointment to Michener when the panel, prevented by partisan infighting from realizing some of its members’ highest-minded hopes for the national celebration, accomplished little before being dissolved in December 1973 — by which time, of course, Nixon himself had plunged the country into an unprecedented constitutional crisis.

Michener “never doubted the country’s resourcefulness, or its ability to survive,” contends Hayes, but believed in the need for a “new set of national goals, a new consensus for America.” Hoping to author a national epic that could heal the wounds of the fractious 1960s and the distrustful Watergate years, Michener returned to the two themes that more than any others endured through all his works — what the scholar George J. Becker, in a 1983 monograph on Michener, identified as “human courage” paired with “human tolerance.”

The Quaker-educated Michener, who credited much of his success to his zeal for exhaustive research and his prolific writing output, consistently sought, wrote Becker, “to emphasize the heroic in human endeavor, to show in all five of his major novels the prodigies of valor, of endurance, of unremitting hard work that ordinary people are capable of.” Even more prominent, from South Pacific onwards, was Michener’s abhorrence of racial prejudice; like earlier novels set in Asia and the Middle East, Becker wrote, both Centennial and the subsequent Chesapeake “face up to the intensity of American racial discrimination, first against Indians, then against imported Negro slaves, and more recently against Mexicans … [and] assert the dignity and worth of so-called inferior races.”

We can view Michener’s pairing of these two values, in the year of Centennial’s publication, as one aging centrist liberal’s attempt to broker a post-Nixonian generational bargain: if the hippies would agree to cut their hair and start holding down jobs, their reactionary antagonists should agree to stop standing in the way of pluralism and multiracial democracy.

It was a simpler task for Michener to craft a narrative around the first idea than the second, if only because it has far more often been the object of American historical scholarship to valorize the pioneer spirit and the Protestant work ethic than to extol the virtues of secular humanist multiculturalism. As Centennial proceeds through the centuries, its plot is driven almost entirely by a series of classically heroic figures in U.S. history — men who, through singular acts of grit or ingenuity, become responsible for key developments in the colonization of Colorado and the West. It’s the bravery of French trapper Pasquinel that opens up the Platte River Valley and its Native tribes to the fur trade. It’s the ambition of cattleman John Skimmerhorn that blazes a trail across the open range and births Colorado’s ranching industry. It’s the pluck of Volga Deutsch immigrant Hans “Potato” Brumbaugh that digs the ditches to irrigate the dry benchlands along the river and make the town of Centennial possible:

[I]t was then that Potato Brumbaugh glimpsed the miracle, the whole marvelous design that could turn The Great American Desert into a rich harvestland. … The once-arid land on the bench proved exceptionally fertile as soon as water was brought to it, and Potato Brumbaugh’s farm became the wonder of Jefferson Territory. As he had foreseen that wintry night on Pikes Peak, it was the farmer, bringing unlikely acreages into cultivation by shrewd devices, who would account for the wealth of the future state.

It’s this last example, especially, that reveals what’s at work in Michener’s parable of the High Plains, since the real-world development of irrigated agriculture in Colorado was famously the product of collective, cooperative visions, not an individual one. With high-profile support from utopian reformers like Horace Greeley, the people of the Union Colony, in pursuit of an egalitarian political project inspired in part by the early socialist thinker Charles Fourier, dug two major irrigation canals in 1870 and cultivated the “Greeley Spud” to feed Colorado’s fast-growing population. Similar efforts were undertaken by the copycat Fort Collins Agricultural Colony two years later, and similar principles were at work in the irrigation ditches dug beginning in the 1850s by Hispano settlers in the San Luis Valley, where the communal acequia system is still in use today.

Why are these things so invisible in Centennial? How can a work of social history be so empty of social movements? In Michener’s telling, each transformative event in the West’s history is necessarily balanced between two extremes of meaning: It must be neither the product of pure randomness, the cold materialist logic of an indifferent universe, nor the fulfillment of some grand design, belonging to a recognizable politics. Instead it must sit at a finely calibrated, market-liberal midpoint: a humble act of self-interest that pioneers a new trade, an individual innovation that confers broad benefits on society, a profit-motivated enterprise that enriches but trickles down. The utopians of the Union Colony, full of a conscious, communal desire to design and build a better world, have no place in such a narrative.

Michener was far from the first writer to shy away from sociological storytelling, and any dramatization of history is bound to rely on compression, allegory and composite characters. But if a primary strength of his work, as defenders like Hayes and Becker argue, is its capacity to educate a mass audience about the past, then it’s fair to evaluate the quality of that education — and not just with regard to the timing of North American interglacial periods, the relative merits of the Hawken and Lancaster rifles, the best breeds to cross with Hereford cattle and other trivia, but about some of the biggest and most important questions we’ve faced as a nation.

II.

Michener deserves credit for the extent of Centennial’s efforts to incorporate the historical perspectives of the Cheyenne and Arapaho into its grand narrative arc, and, well, he knew it; one of the only real uses he gets out of the novel’s framing device is to satirize the magazine editors who brusquely advise Vernor that his story can “safely” begin with the arrival of white settlers in 1844. Centennial’s best stretches come in the patient 300 or so pages that Michener devotes to the Platte River Valley’s long transition from untrammeled wilderness to commercial frontier to bloody borderland to imperial outpost.

It’s not to be taken for granted that any popular novelist telling America’s story in the early 1970s would have gone to such lengths to foreground and humanize the Indigenous people from whom its land was taken, or to confront millions of white readers in middle America with vivid details of the betrayals and atrocities that facilitated this dispossession. At the time of the novel’s publication, the 1864 massacre of hundreds of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho men, women and children by a U.S. Army regiment in southeastern Colorado was still widely known, and even memorialized on a monument outside the state Capitol, as the “Battle of Sand Creek.” Generations of schoolchildren in Colorado and beyond were raised on a version of American history that ignored such acts of brutality altogether.

In Centennial, the location of the Sand Creek Massacre is shifted to the north, and its name and those of its key actors changed, but little else about the event itself is disguised or sanitized. In a book composed of so many interlocking historical currents, there’s no turning point more singular than the arrival of preacher-turned-Army-officer Frank Skimmerhorn, who’s called to the Colorado Territory by a religious epiphany and promptly takes to the newspapers to lay out his mission in stark, biblical terms:

Patient men across this great United States have racked their brains trying to work out some solution for the Indian problem, and at last the answer stands forth so clear that any man even with one eye can see it. The Indian must be exterminated. He has no right to usurp the land that God intended us to make fruitful. … Today everyone cries, “Make Colorado a state!” Only when we have rid ourselves of the red devils will we earn the right to join the other states with honor.

If Skimmerhorn’s messianic, genocidal ravings sound too melodramatically villainous, it’s only to those readers unacquainted with the documented statements of the man he’s based on, U.S. Army Colonel John Chivington, who told his officers that he had “come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians,” or those of newspaperman William Byers, a Chivington ally who used the Rocky Mountain News to endorse a “few months of active extermination against the red devils” a few weeks before the massacre. (Around the same time, the editors of the Nebraska City News urged “a religious extermination of the Indians generally.”) The fictional Skimmerhorn proceeds to issue a declaration of martial law that echoes the historical proclamations of territorial Governor John Evans, who granted Colorado settlers free rein to “pursue, kill, and destroy all hostile Indians that infest the plains” and to “hold to their own private use and benefit all the property” of their victims.

Michener didn’t let his aversion to graphic violence outweigh the need to depict the massacre itself in gruesome detail, including its scalpings, mutilations and Skimmerhorn’s sanctioning of the mass murder of Cheyenne and Arapaho children on the grounds that “nits grow into lice,” another direct Chivington quote. If the Indigenous peoples of Colorado largely disappear from Centennial in the wake of this slaughter, it’s hard to blame that on an author attempting a faithful retelling of history, and Michener’s choice to devote an entire chapter to “The Massacre” at the narrative heart of his Big Book About America suggests there’s ample truth to Skimmerhorn’s prediction that the country could only become what it wished to be, and what it is today, through brutal and knowing acts of genocide.

And yet it doesn’t take long for the ever-patriotic Michener to begin to soften the weight of this judgment. Skimmerhorn, initially a hero to the people of the Colorado Territory for his role in the “battle,” is soon disgraced after shooting an Indian prisoner in the back. Again we see the limitations of Michener’s historical fiction and its reliance, however unavoidable, on load-bearing composite characters. Skimmerhorn is Chivington and Byers and Evans all at once, and as only one man, the forces he represents are more easily defeated and discredited. His march on the Native American camp is portrayed as essentially a rogue operation, enabled by an ill-timed recall of his commanding general to Kansas, when in fact no such circumstance existed (nor had Chivington’s family been victimized by Indians in the Midwest, as Skimmerhorn’s was in another too-neat plot flourish). The last we hear of Skimmerhorn, he’s fled the state, hounded by public scorn for his cowardly deeds. In reality, not even Chivington faced such a degree of accountability — though multiple official investigations reprimanded him for his actions, he eventually returned to Denver and remained a respected figure there until his death from cancer in 1894 — while Byers and Evans still rank among the most venerated figures from Colorado’s pioneer era.

Letting the Skimmerhorn character shoulder all of this is, to be fair, simply the flip side of Michener’s heroicism, a sense that the evils to be found in American history, just like the virtues, belong to the individual, rather than to larger systems and structures. To the extent that Michener considers those systems and structures at all, he is, like any good modernist, inclined to view them with a benign neutrality — as modes of economic and social organization that, if rationally designed, can help human civilization realize its full potential. Just as a well-regulated market mediates and harnesses the power of entrepreneurial capitalism, sorting beneficial productivity and innovation from destructive greed, so do republican institutions mediate and harness the best of the popular will, sorting democracy’s cooperative, egalitarian spirit from the darkest impulses of the mob. It’s classical liberalism’s non-utopian utopia: self-reliance and self-determination, each one the price of the other.

So then where did it all go wrong? Writing a decade after Centennial topped the bestseller lists, Becker noted the contradiction that haunts so many of Michener’s epics: “The novels show a past that is heroic, yet in their last episodes — those dealing with recent or contemporary events — they show a present that is confused, divisive, without coherent purpose or system of values.”

Michener’s great Western saga begins to lose steam as soon as the reader feels the frontier coming to a close, and declines precipitously when the narrative crosses into the 20th century, steamrolling through accounts of industrial beet farming, the Mexican Revolution and the Dust Bowl at a pace that manages to feel both rushed and interminable. But the bottom truly drops out in “November Elegy,” Centennial’s final and most embarrassing chapter. At last Dr. Vernor, arriving in the town of Centennial in late 1973 to finish his magazine assignment, can enter the action — but no sooner has he arrived than his place in the narrative is superseded by another, more aspirational Michener self-insertion.

Paul Garrett, whose introduction comes complete with a full-page family tree identifying him as the improbable descendant of nearly all of the book’s preceding major characters, is Michener’s ultimate fantasy of the Good American, a gruff no-nonsense cattle rancher with an environmentalist streak and a love of Chicano culture, a political Mary Sue who votes mostly for Republicans on the grounds that they “represented the time-honored values of American life” while allowing that “in time of crisis, when real brains were needed to salvage the nation, it was best to place Democrats in office, since they usually showed more imagination.”

Garrett is named chair of the committee planning Colorado’s state centennial celebration, a chance for Michener to rewrite his own dismal personal history with the Bicentennial Commission, but the wish fulfillment doesn’t end there. Soon Garrett accepts another appointment, as chief deputy to the man elected to a newly created statewide office, a position that Michener gives the hysterical title “Commissioner of Resources and Priorities” and describes, without elaboration, as having the authority to “steer the state in making right industrial and ecological choices.”

What follows is Garrett’s whistle-stop tour around early 1970s Colorado, a state grappling with the impacts of environmental destruction, economic inequality, simmering racial tensions, rapid population growth and the looming threat of water shortages. In one or another of his official capacities — before long, they seem to blend together — it’s up to Garrett to deal with each of these problems in turn. In Vail, he warns ski resort operators to expand their runs along the highway corridors, not to “commercialize the back valleys.” In Centennial, where the beet factory has been shuttered and housing developers are moving in, he orders the town’s noxious feedlot to relocate. At a research station in the Cache la Poudre Valley, he plots with hydrologists to curb industrial water use and save Colorado agriculture from the grimmest of futures. On his own ranch, Garrett signs off on a plan to cross his prized purebred Herefords with more efficient and profitable hybrids, and advises his radical Chicano brother-in-law to fight for the revolution by getting a college education: “Learn their system, Ricardo. Beat them over the head with it.”

It would be unfair to say that Michener left readers with the impression that all of the country’s problems could be easily solved, and these vignettes mostly serve as vessels for the author’s humdrum and mostly harmless conservationist moralizing: “This nation is running out of everything,” opines Garrett after one meeting. “We forgot the fact that we’ve always existed in a precarious balance, and now if we don’t protect all the components, we’ll collapse.” But the animating faith behind a message like this is the sense that we’re still masters of our own destiny, that the precariously balanced system being described is still well within our control. If the system was out of balance, we need only tweak the parameters, pull the right sequence of levers, rewrite the code.

From the early overtures of the Enlightenment, all the way through the dizzying heights of utopianism to the harried technocratic tinkering of the late modernists, this faith in the power of reason, in mankind’s mastery over the technologies and systems it had created, endured. But what if it no longer held? What if more and more people began to ask themselves, not without justification, whether the essential condition of their lives was not to be in control of these systems, but to be at the mercy of them?

5. The Miniseries

I.

On any given night in the early 1970s, between 40 and 60 million U.S. households turned on their televisions and picked between the programs airing on CBS, NBC or ABC — unless, of course, a presidential address was being carried by all three. Centennial was just beginning to take shape as an outline in one of Michener’s notebooks on one such night, August 15, 1971, when President Nixon preempted Bonanza to deliver an 18-minute speech that changed the global economy forever.

Nielsen ratings showed that fully two-thirds of all households in America were tuned in as Nixon laid out a new economic agenda, hashed out at Camp David over the preceding three days and spurred by the president’s fear that rising inflation and ballooning Vietnam War debt would lead to a recession and cost him the 1972 election. Months earlier, Nixon had made headlines with the remark that he was “now a Keynesian in economics,” and for the moment it was true enough; on balance, the three-pronged plan outlined in his address, “The Challenge of Peace,” was a sweeping government intervention in the economy, pairing stimulative tax relief with a nationwide freeze on wages and prices.

It was unlike anything the country had seen since World War II — and anything it has seen since. Only in retrospect can Nixon’s program be seen as one of the last gasps of the New Deal order, the bipartisan domestic consensus that government should play an active, central role in the economy to promote the general welfare, and the broader postwar period of international cooperation built upon the same principle. Within a few short years, it would become unthinkable for any American president, let alone a Republican, not just to impose price controls or promise full employment but even to speak of government as if it had the ability or responsibility to do anything of the sort.

In part, that’s the legacy of the third prong in Nixon’s economic plan: the dismantling of the so-called Bretton Woods system of international finance, accomplished by suspending the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold. Though overshadowed domestically at the time by the attention-grabbing (and enormously popular) price controls, it was the unilateral termination of Bretton Woods that reverberated around the world and became known as the Nixon Shock. While the structure established by the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement had been under stress for years, Nixon’s surprise announcement abruptly overthrew an international order that had underpinned the decades of unprecedented prosperity enjoyed by Western democracies and Japan in the mid-20th century, and, in some sense, a system of commodity-backed money that had existed in one form or another for thousands of years.

The causes and effects of the unraveling that followed were complex, and would take years to play out. But Nixon had accomplished the critical delinking of monetary policy from a set of institutions, however imperfect, of democratic, multilateral oversight and accountability. In Europe, wrote the historian Tony Judt in Postwar, the resulting melee of devaluation and free-floating exchange rates “steadily depriv[ed] national governments of their initiative in domestic policy,” an outcome that suited an emerging generation of policymakers just fine:

In the past, if a government opted for a “hard money” strategy by adhering to the gold standard or declining to lower interest rates, it had to answer to its local electorate. But in the circumstances of the later 1970s, a government in London — or Stockholm, or Rome — facing intractable unemployment, or failing industries, or inflationary wage demands, could point helplessly at the terms of an IMF loan, or the rigors of pre-negotiated intra-European exchange rates, and disclaim liability.

In the U.S., too, the stage was set for what a recent book from the historian Fritz Bartel terms “the politics of broken promises,” the shattering of the New Deal consensus and the steady rollback of the midcentury welfare state in all its grand modernist ambition. Any positive effects that Nixon’s plan may have had on the domestic economy were soon rendered moot by the escalating crises of the mid-1970s, chief among them the supercharged inflation brought on by the Arab oil embargo in 1973.

An abundance of cheap oil had been a crucial component of the West’s robust postwar growth, but the embargo, though only in effect for the six months following the Yom Kippur War, ended that era forever. After a sixfold increase in Western oil demand since 1950, the U.S. and its allies found themselves heavily dependent on developing Arab states who were now keen, in a post-Bretton Woods world, to “recapture the value they had lost with the dollar’s decline,” Bartel writes. By the time the embargo was lifted, the price of oil had quadrupled. “With prices already galloping ahead at a steady pace,” he notes, “the fourfold increase in the price of the commodity that formed the basis of industrial society was bound to have dramatic economic effects.”

The end of Bretton Woods further meant that the fallout from economic turmoil in the West and the amassing of vast new pools of oil wealth in the Middle East would now be managed not by a set of international agreements between democratically elected governments, but by an unstable and unregulated new system of supranational capital flows. Global financial markets as we know them today had hardly existed at all in the 30 years of Bretton Woods’ reign, but after “[t]he meteoric rise of financial and energy wealth in the 1970s,” writes Bartel, suddenly their influence could hardly be overstated:

With the world’s surplus capital now at its disposal, the international financial community became an arbiter of politics around the world. … Any nation-state, East or West, that relied on borrowed capital to fund the products of its domestic politics was now subject to the capricious confidence of capitalists. As long as markets remained convinced that borrowed capital could be repaid on time and with interest … [p]oliticians could continue to promise their people prosperity, and the legitimacy of the government could survive unquestioned. But should market confidence ever falter, the domestic politics of borrowing states would be thrown into immediate disarray.

Once unleashed, it was only a matter of time before these forces would spell the ruin of the West’s modern industrialized affluence — strong manufacturing sectors powered by the mass production of Henry Ford, strong middle classes and labor unions protected by the welfare state of John Maynard Keynes. Fordism, wrote the sociologist Simon Clarke, had “promised to sweep away all the archaic residues of pre-capitalist society by subordinating the economy, society and even the human personality to the strict criteria of technical rationality.” But the rise of a truly global capitalism came with a new overriding logic, a new set of efficiencies to be realized. It hardly made rational sense, after all, to locate labor- and energy-intensive manufacturing industries in developed countries with high labor costs and severe dependencies on foreign oil.

What, then, was to become of the American economy as the long shadow of deindustrialization crept over the heartland? With what could it hope to replace the Fordist systems of manufacture that had fueled an era of prosperity unlike anything seen before in U.S. history? Bright minds had already been at work on the answer. At the time of the Nixon Shock, sociologists had spent years theorizing the “postindustrial society,” while management consultants had begun to lecture corporate America on the coming “knowledge economy.” By 1977, the “Information Age” was a concept popular enough for Senator George McGovern, the Democrat Nixon had walloped to win reelection five years earlier, to pen a New York Times op-ed on its implications. “Almost everything we can manufacture can also be made abroad,” wrote McGovern. “Today, there is a school of thought contending that the greatest economic and political resource we have — and one possible difference between future red or black ink in the trade-balance account — is the sale of information and know-how.”

In the ensuing decades, Americans would experience this shift to a service- and information-based economy in a wide variety of ways. They would experience it in factory closings and layoffs and declining wages and lost pensions, in a growing emphasis on the importance of postsecondary education, in the aggressive deregulation of the communications, transportation and financial-services sectors.

Mostly, though, they would experience it through television.

II.

The products of the post-Fordist economy would include TV shows, movies, music, sports and other entertainments, sure, but to a much greater extent they would be lifestyles, consumer goods and the brands and slogans used to sell them to mass audiences. Growth no longer depended on trade balances, assembly-line outputs and economies of scale, but on the ability of a new class of “creatives to defibrillate our jaded sensibilities by acquiring products marginally, but tellingly, different from the last model we bought,” writes the journalist Stuart Jeffries in his book Everything, All the Time, Everywhere. “Fordism may have offered car buyers any color so long as it was black; post-Fordism offers very nearly too many colors, including some that buyers had never heard of.”

Nothing was more essential to the rise of this new economic reality than television, which as an industry quickly underwent an information-age revolution of its own. By the late 1960s the networks had finally rid themselves of an early business model whereby a small handful of corporate sponsors purchased whole timeslots and produced programs to fill them themselves, opting instead for advertiser “scatter plans” and multiple commercial spots per show. In 1971 the networks cut commercials’ minimum duration to 30 seconds from 60, instantly doubling the number of different messages viewers could be bombarded with nightly. Over the next 10 years the advertising revenues of Big Three tripled, and TV executives, under increasingly acute financial pressures from Wall Street, waged a newly frantic war for every last ratings point. “Until the early 1970s, network programmers had relied primarily on hunches to keep attuned to the shifting tastes and attitudes of their audience,” writes the journalist Sally Bedell in Up the Tube, her 1981 history of the decade in television. “But as the financial stakes rose, they hired whole batteries of researchers to produce scientific analyses of popular views and program preferences.”

One consequence was the rapid maturation of scripted television as a popular art form, driven by boundary-pushing creators like Norman Lear. After rejecting its first two pilots, skeptical CBS executives stranded the January 1971 premiere of Lear’s All in the Family in a Tuesday graveyard slot; by the end of the summer it was the highest-rated show in America, a title it would hold for five years running. Its success opened the floodgates for a new generation of primetime shows that steered into the skid of the era’s social and political turbulence, abruptly ending the two-decade reign of provincial sitcoms and variety shows that pandered to conservative rural whites.

It didn’t take long for embattled executives at the Big Three to recognize the potential of All in the Family and its many spinoffs and imitators to better reflect the country’s diversity and draw viewers in with topical material that broke a host of longstanding network taboos. In 1969, Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. had gone off the air without so much as ever having mentioned the Vietnam War; within three years, viewers were offered a fall lineup that included M*A*S*H, its strident antiwar politics only thinly disguised by its Korean War setting, alongside contemporary explorations of race, sex, poverty, mental health, drug use and other issues on sitcoms like Sanford and Son and Lear’s Maude, which featured a special two-episode arc on its title character’s decision to have an abortion.

There are distinct echoes of James Michener in Lear’s long, prolific career, in his hopeful, accommodationist liberalism, and in his uneven reputation among high-culture critics for works that proved massively popular with middle America. Michener himself had briefly ventured into TV writing just as Hawaii went to print in 1959, penning scripts for ABC’s Adventures in Paradise, the first series to be filmed in the 50th state. Though a mild commercial success, the show was panned by critics, and the experience left Michener so embittered that 15 years later, Centennial’s final chapter reserved some of its harshest criticisms for broadcast media and the “illiterate cheapening” they had inflicted on society. “Radio and television could have been profound educative devices,” muses Michener via his hero Paul Garrett. “[I]nstead, most of them were so shockingly bad that a reasonable man could barely tolerate them.”

The creative renaissance of the 1970s raised hopes that television could at last take its rightful place as the instrument of mass moral edification that Michener and other lettered paternalists had dreamed of. As competition between the networks reached a fever pitch, budgets for primetime series soared, and programming executives experimented with attention-grabbing special-event films and miniseries, many of which took on hot-button issues or retold important stories from U.S. and world history. For the better part of a century, the modernists had dreamed of the power of new technologies and ambitious works of art to reshape society for the better. How intoxicating must it have been, then, to glimpse the world’s third-largest country, still healing from the scars of slavery and Jim Crow, tuned in together to the 1977 adaptation of Alex Haley’s Roots, beamed in technicolor into the homes of 130 million people at once?

It was the apex of American monoculture, and it was over almost as soon as it began — but not before NBC, languishing in third place in the ratings, greenlit a 21-hour adaptation of Centennial with a budget of $30 million, five times what Roots had cost ABC.

By the time it debuted in October 1978, Michener’s national epic had missed its moment in more ways than one. The Bicentennial had come and gone without anything remotely like a new consensus. The miniseries’ opening monologue, delivered by Michener against the scenic backdrop of the Grand Tetons and full of moralizing about the country’s responsibility to “this earth we depend upon for life,” was a message the country was well on its way to rejecting. Because of the show’s demanding production schedule, its 12 feature-length episodes were spread out over a period of five months; on its debut it drew fewer than half the viewers that Roots had, and declined from there. Despite sky-high expectations, it ended up as only the 28th-ranked program of the 1978-79 season. NBC sank even lower to record its worst ratings performance in over a decade.

For once, a Michener blockbuster had underwhelmed commercially while mostly winning over the critics — many of whom, at least at first, seem to have been bamboozled by the sheer scale of what NBC had marketed, probably accurately, as “the longest motion picture ever made.” Longtime Los Angeles Times TV writer Cecil Smith proclaimed it “a movie to match its mountains, big and brawny and beautiful as the awesome Colorado Rockies it celebrates,” adding that “[m]ore than any of its predecessors, this is truly a ‘television novel.’” In praise like this, one can detect a certain determination not to let Centennial’s undeniable seriousness go unrewarded. After decades of two-bit screwball westerns and lowbrow country fare, the TV business and its commentariat finally had before them a more grounded and literary rendering of the American mythos to prove the worthiness of the medium. Here was Wild Wild West star Robert Conrad in a hard-nosed dramatic portrayal of French mountain man Pasquinel. Here was no less a symbol of TV’s bumpkin era than Andy Griffith, the sheriff of Mayberry himself, playing against type as tweed-jacketed historian Dr. Vernor.

Mostly, though, Griffith’s arrival in Centennial’s twelfth and final installment just makes the viewer long for a bit of well-written farce and the easy comfort of a laugh track — anything to liven up the slog. Eventually, the spell that show’s ambition had cast on critics wore off just as it had on audiences, and it collected only two nominations and no wins at the 1979 Emmy Awards. Though $30 million could buy an A-list cast and enough cranes, dollies and helicopters to ensure a handful of striking landscape shots per episode, Centennial provides little else in the way of filmmaking artistry. What little compelling narrative texture Michener’s novel had to offer is sanded away into nothing by John Wilder’s scripts and papered over with the hand-holding and melodrama of ultraconventional TV storytelling. (One of Wilder’s only other notable credits in a long small-screen career was 1993’s criminal Return to Lonesome Dove.) The show’s sterile set design and costuming rob its frontier setting of its natural charm, and it’s dated terribly by the cheap cosmetics used to age its key characters through the decades — poor Richard Chamberlain, especially, is forced to spend the latter half of his turn as Scottish trapper Alexander McKeag with the most unsettling ghost-white, glued-on beard the world would see until David Duke’s.

Worse still is the series’ treatment of its Native American characters, the majority of whom are played by white actors in a kind of low-effort redface. Whatever else can be said about Michener’s novel, it devotes nearly one-fifth of its 909 pages to the story of the West before Pasquinel and other white settlers arrive; Wilder and NBC, by contrast, judged that audiences would tolerate fewer than six of the adaptation’s 1,248 minutes.

Unsurprisingly, the series’ most significant and least forgivable revisions to Michener’s tale serve to further ignore and whitewash the history of Native dispossession and genocide, a list of offenses topped by the woeful sequence that concludes episode five, “The Massacre.” While the novel’s ahistorical account of Chivington/Skimmerhorn’s fall from grace was bad enough, Wilder’s adaptation debases it further by inventing a climactic code-of-honor duel between Skimmerhorn and the requisite Good Soldier, Captain Maxwell Mercy, after which the massacre’s perpetrator is banished forever from the territory by his own son. “Skimmerhorn’s driven out of Colorado, out of power, and he’ll never be back. … All the wars are finished,” a remorseful but triumphant Mercy tells Arapaho chief Lost Eagle in the year 1865, promising supply wagons from Denver to save the surviving tribespeople from starvation. Among the series’ final images of Indigenous life is a wide shot of Mercy, gently weeping, and Lost Eagle, holding an American flag, embracing one another beside a cluster of tipis.

It’s an extremely potent symbol — not, of course, of anything remotely having to do with the real history of the West, but of the pathetic inadequacy of a certain brand of self-absolving liberal guilt, and of mass-market entertainment’s unlimited capacity for delusion and deceit.

Students of the Norman Lear school of TV storytelling had hoped, like the literary realists before them, to capture the whole of the human experience, the good and the bad — and believed, even if they wouldn’t admit it in so many words, in the power of these naturalistic narratives to be tools of social improvement. It was John Dos Passos’ old notion of the writer as scientist or engineer, discovering fundamental truths about society and how it functions, celebrating what helps it run smoothly while satirizing and discouraging what ails it.

But what if much of the country didn’t actually want to be confronted with the full truth of its genocidal past? (How many of the millions of Americans who’d made Centennial a bestseller do we really think didn’t just skip those chapters, anyway?) What if the only way for Roots to succeed, in the eyes of ABC brass, was with a massive promotional campaign that marketed the series as a soapy Gone With the Wind-esque plantation story with, as one executive told Bedell, “a lot of white people in the promos”? What if much of the country liked to laugh at, and even laugh with, Archie Bunker’s bigotry every week only so long as neither he nor they learned any lasting lessons about it? Who gets to say what’s good or bad anyway? For the networks, the answer to any and all such questions was automatic: The ratings decide. There were no contradictions worth worrying about so long as they could turn to a simple measure of success in their pitched three-way battle for 200 million pairs of eyes nightly.

By the time Centennial finished its run in February 1979, though, all involved — network execs, Hollywood producers, creative talent and, not least, viewers at home — were growing more and more dissatisfied with the whole arrangement. The ratings war descended into mania; the networks had taken to premiering 20 or more new shows in short runs every fall, then axing most of them after as few as one or two episodes based on overnight Nielsen figures and telephone surveys. The overexposure of made-for-TV movies and showcase miniseries, each one hyped as every bit the must-watch national event as the last, rapidly diminished their power to draw large audiences. After a decade-long development binge, cost-cutting measures returned in force. Low-budget game shows proliferated again. ABC, which had for most of its history been a distant third among the Big Three, surged to #1 with a lineup that relied heavily on the schlock and sex appeal of shows like Charlie’s Angels, The Love Boat and Fantasy Island.

“After twenty-five years of exploitation and repetition, culminating in the excesses of the 1970s, even the most dim-witted viewers began feeling some resentment,” writes Bedell. By the end of the decade, surveys had begun to show that for the first time in the medium’s history, TV viewership was in decline. For a brief historical moment, mass media had given America a genuine popular monoculture — a messy, modern, vulgar, pluralistic, multiracial reflection of itself — before it began to drive people away in disgust.

III.

The great fragmentation that followed wasn’t the product of shifting consumer tastes alone, but of complex new feedback loops created by the technological innovations, economic imperatives and policy reforms of the global information age. By the mid-1980s nearly half of American homes had a VCR, thanks in large part to a booming Japanese consumer electronics industry, and time-shifting and the home video market posed a new threat to the networks’ monopoly on viewers’ attention. The rise of satellite communications systems transformed international news broadcasting and enabled the rise of pay-TV services like HBO and national “superstations” like TBS. Though cable TV had been around in the U.S. in limited, local formats since the late 1940s, a wave of deregulation soon cleared the way for CNN, ESPN, MTV and a long list of other specialized national channels to explode the number of programming options audiences had to choose from. And all of this would be merely a dress rehearsal for the information maelstrom that had been brewing in those years not in the studios of Hollywood or the skyscrapers of Manhattan, but in the laboratories of Silicon Valley.

The hippies had gotten jobs, after all, and many of them saw in the emerging information economy the tools by which the highest hopes of the 1960s counterculture, the dream of a world remade by the liberatory powers of mind-expanding journeys of discovery and kaleidoscopic individualism, could at long last be achieved. Steve Jobs, a longhaired college dropout who’d traveled to India seeking enlightenment and cited Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog as a formative intellectual influence, gave the world the signal declaration of the tech industry’s values in Apple’s famous “1984” ad: the lifeless monotony of dystopian Fordism, the tyrannical horror of belonging to “one people, with one will, one resolve, one cause,” shattered and overthrown forever by the limitless freedom of self-expression the personal computer would offer. In 1995, as the dot-com era dawned, a triumphant Brand made sure readers of Time knew whom to thank for the “cyberrevolution” they were beginning to enjoy. “Reviled by the broader social establishment, hippies found ready acceptance in the world of small business,” he wrote. “The counterculture’s scorn for centralized authority provided the philosophical foundations of … the entire personal-computer revolution.”

Once bitterly at odds with the establishment and with each other, the Boomers were reconciled to both through an economy, and a politics, that joined liberal pluralism to profit-seeking hierarchy. Brand’s generational victory lap came at the height of post-Cold War American triumphalism, and though it was only in 1986 that Czesław Miłosz had spoken for many in the West when he blamed utopianism for the deaths of “innumerable millions,” it didn’t take long after the fall of the Soviet Union for many of those same intellectuals to wonder if humanity had achieved, in liberal democratic capitalism, a history-ending final stage of civilization.

It was a vision not of a modern utopia, but of modern utopianism transcended. Where the master planners had erred, the thinking went, was in believing that society could ever be subordinated to a single vision, no matter how idealistic, no matter how rationally designed. In the final decades of the 20th century, people in the U.S. and other Western countries watched as the great projects of high modernism crumbled around them — in some cases literally, as with the ambitious public housing developments that Le Corbusier and his disciples had helped governments erect in cities around the world.

The sprawling Pruitt-Igoe complex in St. Louis, designed by the Japanese architect Minoru Yamasaki, became one of the first and largest such projects to be demolished beginning in 1972, but it was by no means the last. Seemingly wherever these projects had been built, in the decades that followed they had fallen steadily into disrepair, plagued by poverty and crime, leaving the movement that had inspired them permanently discredited. “Modern Architecture died in St. Louis, Missouri on July 15, 1972, at 3:32 p.m. (or thereabouts),” wrote the critic Charles Jencks in a 1977 book whose title helped popularize a term that had long been floated in art and academia to describe what would come next — The Language of Post-Modern Architecture.

Crucially, the emerging ideologies of the postmodern period located the cause of these failures in key values embedded within modernism itself — in the scope and sincerity of its ambition, in its faith in science and rationality, in its pursuit of objective truth. Architecture’s postmodern critics took an evident joy in identifying the design flaws (Pruitt-Igoe’s efficient but ill-fated skip-stop elevators, the wanton destruction of Robert Moses’ expressways, the logical but lifeless plazas of Le Corbusier’s Chandigarh or Lúcio Costa’s Brasília) that exposed their designers not as impartial arbiters of pure reason but as fallible bureaucrats who’d failed to account for the breadth and multiplicity of the human experience. The theorist James C. Scott collected stories of high-modernist hubris in his 1998 book Seeing Like a State, from experiments with “scientific forestry” in 18th-century Prussia to forced villagization programs in postcolonial Africa. “The progenitors of such plans regarded themselves as far smarter and farseeing than they really were and, at the same time, regarded their subjects as far more stupid and incompetent than they really were,” Scott wrote.

Postmodernism heralded itself as a radical democratizing force, bent on dismantling an ideology that had promised to make things new but instead only reproduced old, old forms of rule of the many by a cruel or incompetent few. Just as suspect as grand architectural or social development projects were the grand narratives of mass culture; postmodern thought meant skepticism not just of authority, but of authorship itself. How could any so-called Great American Novel, almost exclusively the work of upper-middle-class cisgender heterosexual white men, ever hope to represent or speak to the experiences and needs of America’s wildly diverse populace? Why, for that matter, should American matter at all?

It’s hard to imagine a work less prepared to withstand such criticism than Michener’s Centennial, its insistence on a rectilinear, just-the-facts presentation of U.S. history wholly undermined by its glaring blind spots and eventual descent into heavy-handed lecturing. For all the artifices of high modernism, for all its gestures towards rationalism and systematization, at the end of the day there was only ever a flawed, flesh-and-blood individual at the controls of the machine, attempting to tell the masses where and how to live or what core values America stood for. Not for nothing did several consecutive generations know the 20th century’s archetypal oppressor as Big Brother, or simply The Man.

By contrast, postmodernity promised true liberation not through the establishment of a new order but through the effacement and erasure of order altogether, supplanted by the mesmerizing chaos produced by the information economy and increasingly decentralized communications technology. By its nature, postmodern culture was infinitely variable in its appeal, crossing ideological and generational lines as it drew consumers of the cable-TV and internet ages into insular ecosystems where their individual interests and values could be endlessly reflected back to them. To the punks, the ironists, the avant-garde, it imbued experimentation and iconoclasm with new artistic merit and political urgency. To theorists in the academy, and to people belonging to long-oppressed demographic groups, it meant the emergence of a wide array of emancipatory ideologies that aimed to deconstruct harmful binaries and power relations. The postmodern critique of the modern was persuasive and expansive enough to win over both anarchists like Scott and world-conquering capitalist entrepreneurs like Jobs, and the lessons drawn from all this never needed to be especially coherent: “Our generation proved in cyberspace that where self-reliance leads, resilience follows,” declared Brand in 1995, “and where generosity leads, prosperity follows.”

And yet many, many Americans did not find the experience of the postindustrial economy to be quite so liberating or prosperous. Perhaps this was most acutely true of the factory workers and Rust Belt towns who were among the earliest and most obvious losers of globalization, but it was by no means limited to them. From a psychological standpoint alone, the era came with new compulsions and social pressures, new modes of stress and alienation, new paradoxes of choice. To live in the information age has meant being surrounded at all times by an exhausting cacophony of language and image, much of it designed for the express purpose of manipulating our cultural tastes and consumer habits.

More to the point, for many people in the U.S. and other Western countries it has meant believing, often with very good reason, that things have come unstuck — that too much of the information we encounter no longer bears any meaningful relation to the material world, and that beneath the noise of all the promotional bluster and insistent hard sells and aspirational lifestyle marketing we’re deluged with, in one key way or another our lives are getting not better but worse.

Not surprisingly, it was literature that proved best able to anticipate and give shape to this feeling. Even before postmodernism had a name, a small handful of writers had swan-dived into the torrents of language cascading through the information economy and surfaced performing exhilarating genre experiments and acrobatic feats of prose. They were stylists whose virtuosic facility with language granted them a kind of backdoor into the rapidly assembling source code of the postindustrial age: for Thomas Pynchon, it was the carnival-barker gab of midcentury ad men and the epigrammatic menace of the ascendant security state; for William Gaddis, it was the unbearable accumulated weight of two millennia of Western artistic tradition and Christian religious doctrine. Even Dos Passos, as early as the 1930s, had prefigured many of the moods and methods of postmodern literature with U.S.A.’s collages of newsreel excerpts, short biographies and experimental “Camera Eye” segments, the frantic social and political currents of the era channeled through prose heavy on nonstandard compound words and long breathless sentences that heighten the sense of anxiety and overload. The novel’s characters are sailors and stevedores, aristocrats and actresses, labor organizers and P.R. pros, but they all share a certain helplessness, finding themselves continually adrift on world-encircling tides of commerce and conflict that they could never hope to control.