Inheriting the earth

Estes Park, the Earl of Dunraven and the West's forgotten history of aristocrat land grabs

park, n. — from the French parc, probably from the Medieval Latin parricus, “fence”: an enclosure of land. A word whose usage has been flipped on its head by the advent of modern egalitarianism; it referred originally to a private hunting ground reserved for the exclusive use of a monarch or lord. Now, of course, the word is understood around the world to mean something like its feudal-era opposite, the commons, land publicly owned for the benefit of all.

It was somewhere in the middle of this shift that park acquired another meaning, unique to the central Rocky Mountains of Colorado and Wyoming. The French fur trappers who became some of the first white men to explore the region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries used the word to describe the alpine basins that sustained great herds of deer, elk and other game, giving us not only the world-famous South Park, but its cousins North Park and Middle Park, and smaller place names too.

“Parks innumerable are scattered throughout the mountains, most of them unnamed, and others nicknamed by the hunters or trappers who have made them their temporary resorts,” explained the British explorer Isabella Bird during her ascent into one of them, Estes Park, in 1873. For Bird and others, the scale and abundance of these mountain wildernesses could only be compared to the trappings of aristocratic wealth — they were, wrote Bird in a letter collected in A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, “parks so beautifully arranged by nature that I momentarily expected to come upon some stately mansion”:

Here, in the early morning, deer, bighorn, and the stately elk, come down to feed, and there, in the night, prowl and growl the Rocky Mountain lion, the grizzly bear, and the cowardly wolf. There were chasms of immense depth, dark with the indigo gloom of pines, and mountains with snow gleaming on their splintered crests, loveliness to bewilder and grandeur to awe, and still streams and shady pools, and cool depths of shadow; mountains again, dense with pines, among which patches of aspen gleamed like gold.

Today, the high meadowlands settled by Joel Estes in 1859 serve as the main entrance to a park in the modern sense of the word, Rocky Mountain National Park, the crown jewel of Colorado’s public lands and the third most visited national park in the country. But in an episode now mostly forgotten, much of the same land was the site of an unlikely — and, for a time, successful — scheme to establish the older, more medieval kind of park, complete with its very own British noble.

The Earl of Dunraven, Windham Thomas Wyndham-Quin, first visited Estes Park in 1872, “with his guests, Sir William Cummings and Earl Fitzpatrick,” on big-game hunting expeditions, recalled Enos A. Mills in his 1905 history of the region. “Dunraven was so delighted with the abundance of game and the beauty and grandeur of the scenes that he determined to have Estes Park as a game preserve.”

It possibly wasn’t his first choice. With the help of guides like Buffalo Bill Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro, Dunraven and his companions roamed all over the West in those years, including the Yellowstone region, becoming some of its first-ever tourists. “To no part of the Great West should I sooner advise the traveler to go than to that marvelous country,” he wrote in a memoir of his hunting expeditions decades later. Though Yellowstone had only been formally surveyed in 1871, within a year it was withdrawn from public auction and designated as America’s first national park. “It is, as auctioneers would say, a most desirable park-like property,” Dunraven wrote, “and, if Government had not promptly stepped in, it would have been pounced upon by speculators.” In light of what he attempted in Colorado in the ensuing years, his words seem rueful.

The Earl of Dunraven’s presence on the far frontiers of the Wild West was less extraordinary than it might seem. While the escapades of upper-class Americans like Teddy Roosevelt who traveled West to play cowboy are well enough remembered today, there’s less appreciation for the equally rich tradition of European and especially British aristocrats who did the same.

“The American West exercised a particularly strong pull on members of the British landed classes, the titled aristocracy and gentry who for centuries had held a dominant position in British society,” writes Monica Rico in her study of the phenomenon, Nature’s Noblemen. It was a pull only made stronger by the world-spanning social upheavals of the 19th century: “In the American West,” Rico writes, “upper-class British men could imagine themselves temporarily liberated from the expectations of imperial governance. They could regress into boyhood and emerge renewed. The West was a realm of desire, pleasure, and freedom.”

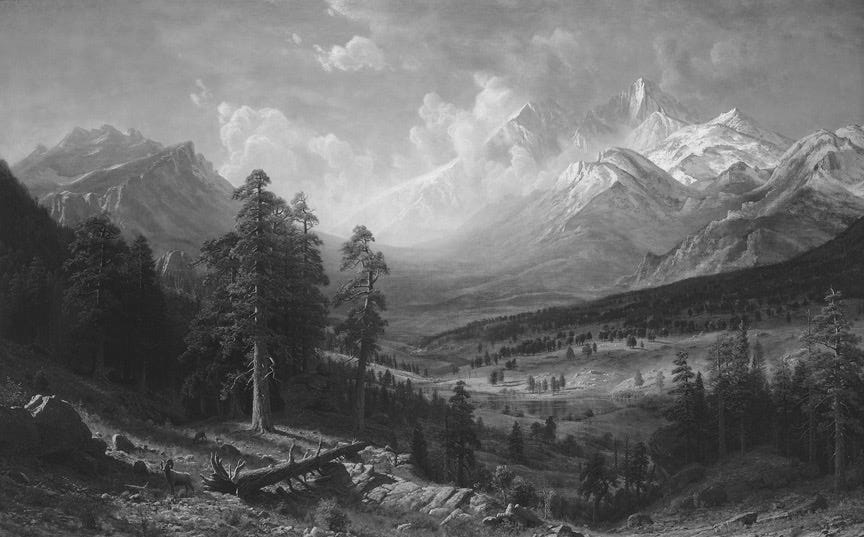

Men like Dunraven, Sir William Drummond Stewart, Moreton Frewen and a long list of others played a small but important role in establishing the new mythos of the West, penning widely-read travelogues and offering patronage to foundational frontier painters like Albert Bierstadt and Alfred Jacob Miller — and, of course, leaving their mark on the land in the process. In 1854, Sir St. George Gore, a wealthy Irish baronet, set off across the plains from St. Louis with 40 servants in tow, beginning a grand hunting expedition that lasted three years and cost an estimated $100,000. He slaughtered so many thousands of buffalo that Indigenous tribes lodged a formal complaint in Washington and the incident became a minor diplomatic row. Forty years later, Cody recalled Gore’s reaction in a piece for Cosmopolitan: “He actually proposed to Uncle Sam to whip the entire Sioux nation at his own expense, and vowed that he could, in thirty days, equip a little army of his own, which would wipe those murderous thieves from the face of the earth.”

Unsurprisingly, behavior like this often mystified and embittered working-class Americans. Peter Pagnamenta’s Prairie Fever quotes a report from a Western correspondent for the New York Times in the year that Gore began his expedition:

St. Louis has been, and is yet, much bored and victimized by foreign noblemen and quasi-noblemen, who pass through, stopping for some time preparatory to a hunting tour through the Rocky Mountains. It would seem that the younger sons and illegitimate offspring of the scions of the English Aristocracy get tired, as too tame, of shooting quail and pheasants at home, and yearly come out here to shoot buffalo on the Plains.

So it was with Dunraven some 20 years later in Estes Park. As a foreigner, the Earl was prohibited from claiming any part of the vast federal territories of the West for himself under the Homestead Act, but that proved little impediment as his agents set to work parading drifters and saloon toughs through the land office in Denver, filing fraudulent claims on dozens of 160-acre parcels that were then sold to Dunraven’s Estes Park Company. Although the tactics were an open secret, and locals were furious — “one of the most barefaced land steals of this land-stealing age,” seethed the Larimer County Express in August 1874 — a grand jury investigation launched by the U.S. Attorney in Denver went nowhere.

Dunraven’s plot almost certainly involved a measure of violent intimidation; it seems to have figured centrally in the 1874 death of James Nugent, known as “Rocky Mountain Jim,” whose fabled romance with Bird during her stay in Estes Park a year earlier has become a celebrated piece of local lore. Reportedly as a result of some kind of drunken altercation, Nugent was shot by Griff Evans, a homesteader known to be in Dunraven’s employ. Evans claimed self-defense and was acquitted thanks to the testimony of a key witness, William Haigh, another wealthy Englishman and an associate of the Earl’s. Mills quoted the “consensus” view among Estes homesteaders: “English gold killed Jim for opposing the land scheme.” Though the accusations of Dunraven’s involvement, including one made by Nugent on his deathbed, were well-known and printed in Colorado papers at the time, the Earl wrote blithely of the incident in his memoirs decades later, attributing the fatal duel to a feud over Evans’ daughter and reporting: “no casualties on our side.”

Just a few years after Yellowstone had been established in a historic act of foresight, another spectacular expanse of Rocky Mountain wilderness had fallen victim to exactly the kind of privatization that early conservationists had feared in the Montana Territory. The Denver Tribune published a clear-eyed assessment of Dunraven’s land grab shortly after it was exposed in the summer of 1874:

The question then arises whether the people of Colorado will permit one of the richest and most attractive portions of the Territory to be set apart for the exclusive benefit and behoof of a few English aristocrats, or whether the Government itself shall keep its title to the park, pass stringent laws relating to the fish and game, and so have this broad and lovely domain kept as a National ‘Institution,’ of a general benefit to the people of Colorado.

But despite the initial uproar, Colorado, in the years before and after it won statehood in 1876, came to accept the former choice. Precisely estimating the size of the estate amassed through Dunraven’s fraud is difficult, in part because much of the land was strategically chosen to give him control over a much larger area; Mills wrote that he claimed about 15,000 acres, while newspaper accounts from the period put the figure at 38,000 or higher. For the better part of a decade, Dunraven split time between his homes in Ireland and Colorado, becoming a fixture in the Centennial State’s burgeoning elite and organizing social clubs and joint business ventures with other wealthy British expats in Colorado Springs. In what was perhaps one of the first Colorado travel guides ever written, published by the British magazine The Field in 1879, the authors referred to his mountain fiefdom, “Estes Park, the charming and picturesque seat of Lord Dunraven.”

Unlike in Yellowstone, it would take nearly half a century for the Tribune’s vision of a national park to become reality. Likely from a combination of legal challenges and the steady inflow of other tourists and homesteaders, Dunraven eventually conceded defeat. “It became evident that we were not to be left monarchs of all we surveyed,” he wrote with an indeterminable degree of irony. “People came in disputing claims, kicking up rows; exorbitant land taxes got into arrears; we were in constant litigation.” He opened up a hotel on the property, and soon stopped visiting altogether. It wasn’t until 1908, however, that he sold off his holdings to F.O. Stanley, an early automobile tycoon. Stanley’s acquisition of the valley’s largest and best-situated parcel, wrote Mills, was “the epoch-making event” in the valley’s history, paving the way for the investment in hotels, roads and other infrastructure that led to the park’s establishment seven years later.

All’s well that ends well, then? The Earl’s brief reign left no lasting mark on Estes Park, and today a quarter million acres of breathtaking Rocky Mountain wilderness remain preserved for all to enjoy. But Dunraven’s scheme was only one small part of a wave of upper-class British tourism and immigration to the West in the late 19th century, which was itself only the most outward sign of a much deeper current: the flow of huge amounts of British wealth into newly-opened Western lands and infrastructure. The farms and cattle ranches and railroads of the rapidly populating plains and mountains needed startup capital, after all, and the landed classes of the Old World, awash in inherited fortunes and cheap credit, became some of the most dependable sources of it.

For aristocratic families who felt overtaken by the forces of commercialization and industrialization, investment in vast agricultural estates had an appealing familiarity to it. More than 30 Western ranching and land companies were traded on the London Stock Exchange in the 1880s, a dozen of them in Texas alone. “The list of those who took large stakes in companies and syndicates included Lord Aberdeen, Lord Airlie, the Duke of Argyll and his son Lord George Campbell, Lord Castletown, the Earl of Dunmore, the Earl of Ilchester, Lord Neville, the Earl of Strathmore, the Marquis of Tweeddale, and a pack of others,” writes Pagnamenta. No less a figure than the legendary Texas cattleman Charles Goodnight — the inspiration for everything from early frontier ballads to Lonesome Dove — prospered thanks in large part to his partnership with Jack Adair, the wealthy Irish landowner for whom Goodnight’s JA Ranch was named.

“There is no doubt but lands in America are considered good investments by English capitalists,” the Greeley Tribune had written in 1871, reporting that “many thousand acres have been purchased between Denver and Colorado City, mainly with English money.” With blithe optimism, however, the Tribune assured its readers that this inrush of deep-pocketed aristocrats posed no real threat to the common homesteader, placing its faith in the free-soil, free-labor ideology that so animated American liberals in the decades surrounding the Civil War: “Let no one fear that we shall have a landed monopoly… Labor, improvements, and population make land desirable, not money. These English capitalists make the great mistake in supposing that if they get land the same relations will exist between them and the laborer that exists in England. If a man, here in the West, is worth anything on a farm, he will be certain to have a farm of his own.”

It was a nice thought. But little over the next two decades stopped the British upper classes from gobbling up Western land. Their schemes varied in character, from George Grant’s idealistic farming colony in Kansas, spanning a hundred thousand acres and named Victoria in honor of his sovereign, to the more ruthlessly managed holdings of William Scully, who had already gained notoriety for his cruel treatment of tenant farmers on the lands he inherited in his native Ireland before he acquired nearly a quarter-million acres across Illinois, Kansas and Nebraska in the 1870s. Most such estates were amassed through the same underhanded tactics that Dunraven used, with fraudulent land claims arranged in checkerboard patterns and strategically placed along watercourses to give their owners effective control over vast areas. By the mid-1880s, Britons were estimated to control more than 15% of the U.S. cattle trade, with the percentage far higher in free-range states like Wyoming, and an Interior Department report on holdings by “foreign noblemen” identified two dozen individuals and syndicates controlling nearly 21 million acres of land.

It was quite possibly this brush with the feudal past, in the terra nova of the rural West and the Great Plains, that made those regions such hotbeds of radicalism in the final decades of the 19th century. Tenants targeted Scully with boycotts and rent strikes, and homesteaders who joined Granges and Farmers’ Alliances railed against agricultural monopolies and absentee landlordism. “It is astonishing, but true, that alien landlords own millions of acres of American soil,” thundered Terence Powderly, leader of the Knights of Labor, in an 1883 convention speech. “I recognize no right in the part of the aristocracy of the old or new worlds to own our lands. We fought to hold them once, and if it is necessary I am willing to advocate the same measures again.”

Though it’s a little-used trope today, the villainous British aristocrat appeared often in early Western fiction. In her 1886 novel, Waverland: A Tale of Our Coming Landlords, Sarah M. Brigham moralized against “foreign land robbers in the great West,” including Lord Sanders, a lightly fictionalized Scully. Charles King’s Dunraven Ranch, serialized in Lippincott’s in 1888, borrowed the Earl’s name but transported his estate to West Texas cattle country, where the lord’s thuggish, thickly-accented ranch hands clash with a newly arrived U.S. Army regiment. “I’ve often heard an Englishman’s house was his castle,” muses our cavalry-lieutenant hero upon arrival, “but who would have thought of staking and wiring in half a county — half a Texas county — in this hoggish way?”

The populists’ crusade reached the halls of Congress, where members vowed action. “Are we the servile and supple tools of foreign capitalists, or are we going to preserve the country for our own people?” asked Rep. James Belford of Colorado on the House floor. But legislation to address the issue got bogged down for years; powerful emerging industrial interests were in no rush, it turned out, to shut off a ready source of free-flowing capital. Tellingly, opponents blocked one early attempt at a fix on the grounds that it was “too broadly drawn, and damaging because it would exclude foreign investment from other areas, like mining and railways, where it was still appreciated,” Pagnamenta writes; when an Alien Land Act was finally passed in 1887, it was “criticized for being mild and toothless.”

It took forces larger than congressional action to finally curb the great aristocratic land grab, starting with the decline of the Western cattle boom in the late 1880s. Industrialization and urbanization continued apace, and the simple fact was that land, especially land beyond the 100th meridian in the arid West, was no longer the engine of wealth that it had been for much of human history. States joined the federal government in passing laws that made it more difficult to claim large new estates, but by then few rich foreigners were interested anyway.

Of course, that’s not to say that all the lords of the Old World packed up and went home, or that transatlantic investment stopped altogether. The more forward-thinking noblemen were those like Baron Walter von Richthofen, scion of a powerful German family who arrived in Denver in 1878. Richthofen invested in cattle, mining, railroads, real estate, racehorses, beer gardens and more; many of his ventures failed, but he was rich enough that it didn’t matter, and in 1886 he built the 15,000-square-foot Richthofen Castle on the eastern outskirts of the city. He became a founding member of the Denver Chamber of Commerce, and like so many other upper-class immigrants of the era, blended seamlessly into America’s burgeoning, homegrown industrialist elite, partnering with other early Colorado tycoons like Horace Tabor and William Loveland. Amid the soaring inequality of the Gilded Age, it was no great leap for so many of these men to become known as barons of one kind or another.

While the populists of the West may have succeeded in defeating a specific kind of neo-manorialism, their larger struggle against landlords and monopolists ended far less conclusively. “As Americans we are utterly and resolutely opposed to English ideas of caste,” declared the Castle Rock Journal in 1887. “We want no caste, no upper classes, no ‘lower orders.’ We should unite in trying to stamp out feudalism and flunkeyism.” But in the long run, simple plutocracy has proven just as effective as hidebound laws of ennoblement and primogeniture at maintaining rigid social and economic strata.

In few places is that more obvious than the modern West. Dunraven was ahead of his time in treasuring the region chiefly for its recreational and aesthetic value, rather than as an engine of industry. Today, the Earl who so coveted Yellowstone as a private sanctuary would blush at the situation in surrounding Teton County, Wyoming, which has been transformed by an influx of the ultra-wealthy into the country’s single most unequal community. “In the richest county in the richest nation in the world,” writes Justin Farrell in his 2020 book on the area, Billionaire Wilderness, “there are homeless kids who attend the local high school, multiple families living wedged into a single motel room, a quarter of all kids receiving free or reduced lunch and breakfast.” Across the Montana state line lies the ultra-exclusive Yellowstone Club, a private ski and golf resort where the average home is priced at $18 million. There’s hardly a billionaire alive today who doesn’t have a luxury property somewhere in the West, though not all of them are quite as tragicomic as Gunnison County, Colorado’s Bear Ranch, where Bill Koch — son of an oil baron, grandson of a railroad baron, brother of Charles and David — has built a literal, full-size, 50-building Wild West town for his private enjoyment.

It should come as no surprise that amid another American age of rampant monopolism and consolidation of wealth, these trends are accelerating. In 2019, the Land Report calculated that the country’s 100 largest landowners controlled 42 million acres nationwide, a 50% jump in just over a decade. New money joins old, and the gears keep turning. The bulk of William Scully’s lands are still in the hands of his great-grandchildren, who are keeping up with modern trends: “All Scully heirs seem to have interest in organics,” one enthusiastic farm manager told the Peoria Community Word in 2016. Jack Adair’s great-great-grandchildren still own the JA Ranch. Richthofen Castle remains standing, surrounded by modest suburban ranch homes in east Denver, and its current occupants maintain a website that distills two and a half centuries’ worth of this country’s incoherent views on class into 13 dissertation-worthy words: “We’re your average American family living in a not-so-average American castle.”

Dunraven Ranch, King’s would-be sendup of the Earl of Estes Park, ends not, as one might imagine, with the brave American cavalrymen defeating and expelling the “hoggish” Brits from their ill-gotten domain. Instead, in a baffling twist, our hero’s friend, an unassuming Army sergeant, is revealed to be the owner’s long-lost son and heir. He takes his rightful place as lord of the manor, marries his sister to our hero, and everyone lives happily ever after. “Down at Dunraven,” the tale concludes, “the gates are gone, the doors are ever hospitably open” — not because the reign of silver-spooned robber barons has ended, but because one of the good ones has come along. Just as often as Americans have dreamed of overthrowing the aristocracy, they’ve settled for promises that they might one day join it.