‘Roughing It’ and the Western roots of the American voice

Or, why it wasn't Bret Harte who ended up being taught to every English student in the country

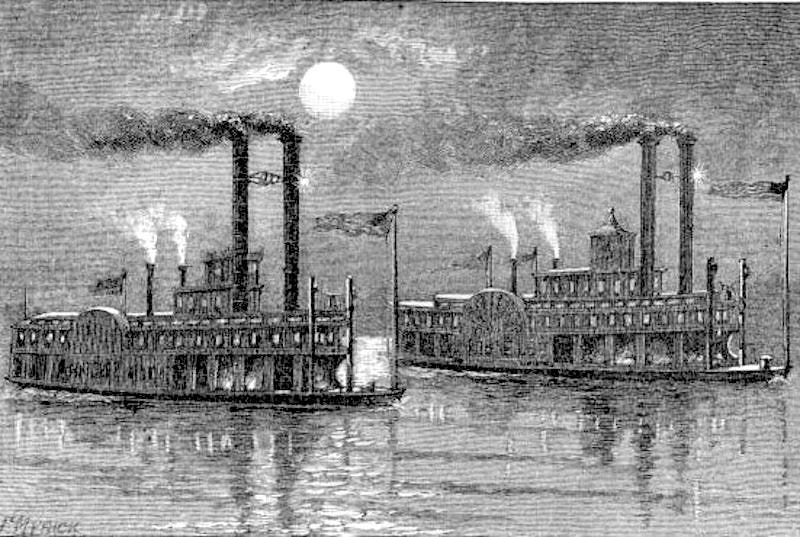

The Mississippi River steamer Nebraska arrived in St. Louis late in the evening on May 21, 1861, delivering 25-year-old Sam Clemens into a city riven by the onset of the Civil War. The Nebraska, which had left New Orleans a week earlier, had been among the last civilian vessels allowed north through the Union blockade at Memphis, and now Clemens, who had once thought he’d found a lifelong vocation as a steamboat pilot, had a series of pivotal decisions to make — starting with which side to take in the conflict over slavery that was rapidly engulfing the country. Like the state in which he was born, Clemens’ loyalties were muddled; for a few weeks in June, he joined some friends from his hometown in a ragtag secessionist militia, but soon deserted. In July, when his brother Orion, a loyal Lincoln Republican who’d nabbed a minor sinecure as secretary to the governor of the Nevada Territory, offered him a chance to escape to the West, Clemens leapt at it.

None of this history appears in Roughing It, the Western travelogue that Clemens, who by then had adopted the pen name Mark Twain, published a decade later. In nearly 600 pages chronicling the years 1861 to 1867, the Civil War is alluded to only once or twice in passing. If anyone ever needed proof of the 19th-century frontier’s function as America’s safety valve, letting tensions between North and South dissipate westward, here was the West serving as a place where one of its most celebrated artists — destined to play a leading literary role in its moral reckoning with the horrors of slavery — could hide out and pretend that the singular event of both his lifetime and the country’s history simply didn’t exist.

The thing I’m most excited to do with this newsletter is explore overlooked stories and underrepresented voices in the literature of the West. But as a Missouri kid come west, writing a newsletter whose title is half-inspired by the last line of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, it was never going to be long before I used it as an excuse to read Roughing It for the first time.

When I did, I was immediately struck, like I am every time I go back to Mark Twain, by the familiarity of the prose — its sense of continuity with just about every other piece of American writing published in the last 150 years or so. Reading Hawthorne or Melville from just a decade or two prior can feel archaeological, an act of dusting off faded vocabularies and cobwebbed syntaxes to try to get a glimpse at the past; the same can be said for many of Clemens’ contemporaries, even some of those he’s most closely associated with, who gave into the gravitational pull of the Boston Brahmins and their stiff, continental conservatism. But Roughing It, like much of Twain’s other work, reads like something that could have been published in an American magazine at any point in the last century and a half. Clemens left behind the constraints of Eastern formality and in the wilds of the West found a voice — arch, conversational, documentary, self-aware — that’s echoed through American literature ever since. Mark Twain, the not-quite-alter-ego that Clemens invented in the Nevada Territory in 1863, didn’t leave behind the Wild West’s most vivid portrait of a desert mountainside or its most visceral account of a barroom shootout, but it’s that voice, more than anything else, that makes Roughing It feel more alive than perhaps any other text that survives from the period. Mark Twain: pretty good writer.

As a boy, Clemens had been among the first American schoolchildren to learn English from the McGuffey’s Readers, an unorthodox series of textbooks authored by an itinerant Ohio grammar-school teacher and first published in 1836. For the emerging American middle class, the Readers replaced the New England Primer and other colonial-era tomes that relied on rote memorization and harsh, Puritan didacticism, instead offering young learners a more immersive approach that blended vocabulary and grammar lessons with passages from the Bible, Shakespeare, poetry and popular fiction. Hawked by traveling salesmen to families and teachers across the rapidly populating American countryside, the Readers would go on to sell an estimated 120 million copies and produce, writes Twain biographer Ron Powers, “the first mass-educated and mass-literate generation in the modern world.”

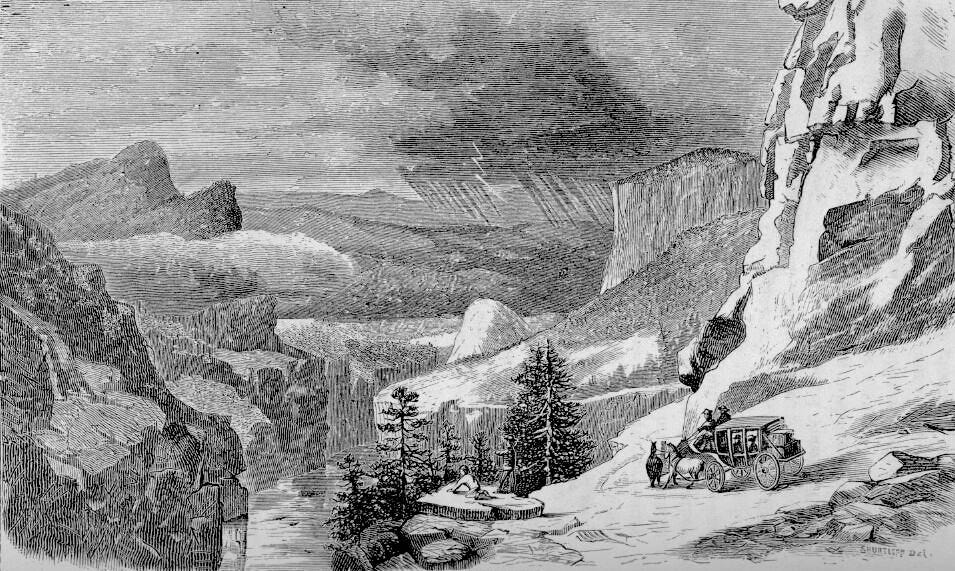

Of course, Mark Twain did much more than just passively slip mid-stream into a new, more voluminous current of American language; he did more than anyone else to chart a path towards, as Powers puts it, “purging American literary English of its heavy Victorian ornamentation.” In a memorable bit of stranger-than-fiction metaphor recounted in Roughing It’s opening chapters, Clemens and his brother made their stagecoach trip across the plains weighed down by ten pounds of U.S. federal statutes and an unabridged dictionary in their luggage. “Every time we avalanched from one end of the stage to the other,” Twain writes, “the Unabridged Dictionary would come too; and every time it came it damaged somebody.” Though Roughing It was only Twain’s second published full-length manuscript, it shows him already having come into his own as his country’s foremost folk linguist, a self-taught literary critic with a masterful ear for the peculiarities of American speech. Twain’s travelogue is as much of a guide to the geography and wildlife of the West as it is a primer for “the vigorous new vernacular of the occidental plains and mountains”; he writes of a traveler who “rained the nine parts of speech [in] a desolating deluge of trivial gossip,” and of a drunk who spoke by “every now and then tugging out a ragged word by the roots that had more hiccups than syllables in it.”

After a year spent failing to make his fortune in either silver or timber, Clemens began his writing career in earnest in September 1862 as a correspondent for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, and by the following February, in a series of dispatches from the legislature in Carson, he was signing off as “Mark Twain,” a reference to his riverboating days. It was in Nevada, and later San Francisco, where he first rubbed elbows with some of the era’s best-known writers, including Artemus Ward, who came through Virginia City on a lecture tour and encouraged Clemens to submit his work to Eastern papers, and Bret Harte, who edited him at The Golden Era, California’s first true literary journal.

Clemens would spend the early stages of his career in Harte’s shadow, grateful for his mentorship but increasingly envious of his celebrity. The New York-born Harte had arrived in the Golden State as a 17-year-old in 1853, and he was among the first Western writers to catch the eye of the Eastern literary establishment, enrapturing audiences with exotic accounts of life among the forty-niners. His best-known short story, “The Luck of Roaring Camp,” told the tale of an infant child raised by the men of a hardscrabble mining outpost:

Tipton proposed that they should send the child to Red Dog — a distance of forty miles — where female attention could be procured. But the unlucky suggestion met with fierce and unanimous opposition. It was evident that no plan which entailed parting from their new acquisition would for a moment be entertained. “Besides,” said Tom Ryder, “them fellows at Red Dog would swap it, and ring in somebody else on us.” A disbelief in the honesty of other camps prevailed at Roaring Camp, as in other places. …

By the time he was a month old the necessity of giving him a name became apparent. He had generally been known as “The Kid,” “Stumpy's Boy,” “The Coyote” (an allusion to his vocal powers), and even by Kentuck's endearing diminutive of “The d—d little cuss.” But these were felt to be vague and unsatisfactory, and were at last dismissed under another influence. Gamblers and adventurers are generally superstitious, and Oakhurst one day declared that the baby had brought “the luck” to Roaring Camp. It was certain that of late they had been successful. “Luck” was the name agreed upon, with the prefix of Tommy for greater convenience. No allusion was made to the mother, and the father was unknown. "It's better," said the philosophical Oakhurst, “to take a fresh deal all round. Call him Luck, and start him fair.”

Maybe you’ve never read anything by Bret Harte before, and sure, it’s cruel to judge any writer on the basis of a couple paragraphs … but you can hear it, right? The dissonance, the quasi-humor, the awkward ventriloquy, the narration that can’t quite locate itself in relation to the action. Them fellows. Harte’s stories are full of what Twain, in a drive-by skewering of James Fenimore Cooper midway through Roughing It, called “just such an attempt to talk like a hunter or a mountaineer as a Broadway clerk might make after … studying frontier life at the Bowery Theatre a couple of weeks.”

Perhaps only Clemens, with his genius for language as it was actually spoken, could have heard the cacophony of voices marching across the continent, in a country literally at war with itself, and managed to synthesize it all into something intelligible. “All the peoples of the earth had representative adventurers in the Silverland,” he wrote excitedly in Roughing It, “and as each adventurer had brought the slang of his nation or his locality with him, the combination made the slang of Nevada the richest and the most infinitely varied and copious that had ever existed anywhere in the world.” Twain, like Harte, would eventually leave the West in search of fame and fortune among the Brahmins, but he would succeed where Harte failed in large part because his time in the silver camps and goldfields, in Powers’ words, “awoke him to the ecstasies of an expressive style unthinkable to the saints of literature back east.” In 1865’s “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog,” a short sketch that was written at Ward’s urging and gave Twain his first taste of national acclaim, a prim Eastern narrator introduces the frame story and then steps aside, letting an old forty-niner tell his tale in fluent slang: “I let him go on in his own way, and never interrupted him once.”

As Twain eclipsed his old mentor, it was Harte’s turn to feel jealousy. He borrowed money constantly from his writer friends, including Clemens, and begged him to collaborate on various projects; the pair ultimately fell out over a disastrous attempt to co-write a play in 1877. Clemens, who had just a few years earlier credited Harte for having “trimmed & trained & schooled me patiently until he changed me from an awkward utterer of coarse grotesqueness” to the country’s most famous author, carried to his grave a grudge against the man he now called “a snob, a sot, a sponge, a coward, a Jeremy Diddler.” Harte’s flight eastward eventually took him all the way across the Atlantic, where he lived out his days peddling Gold Rush tales to European audiences for whom they still had some novelty. For five dollars, I picked up a 1947 collection of his short stories in a bookstore a few weeks ago, and even its introduction, a mild attempt at rehabilitation, concedes that by the time he settled in London, Harte was “an overworked hack, scraping the bottom of the California barrel to turn out his thousand words a day.”

It was Mark Twain, instead, who achieved Harte’s dream of acceptance by literary gatekeepers like William Dean Howells, editor of The Atlantic, who perhaps had his friend Clemens in mind when, in 1880, he described “the best sort of American” as a “Westerner … with Eastern finish.” It was Mark Twain who secured a place in the canon by injecting some much-needed populist realism into American letters. It was Mark Twain, wrote historian Vernon Louis Parrington in 1930, who finally gave the country a literary tradition that was wholly its own:

Here at last was an authentic American — a native writer thinking his own thoughts, using his own eyes, speaking his own dialect — everything European fallen away, the last shred of feudal culture gone … the very embodiment of the turbulent frontier that had long been shaping a native psychology, and that now at last was turning eastward to Americanize the Atlantic seaboard.

Of course, what’s meant by American and Americanize is a more fraught question than even a Progressive polemicist like Parrington thought it was a century ago. What kind of “psychology,” exactly, did that “turbulent frontier” produce? What did Samuel Clemens find out West, and bring with him back to the East, under a different name, in a new voice?

While Clemens, who a few weeks before buying his stagecoach tickets had taken up arms for the Confederacy, would go on to be something like the country’s imperfect literary conscience on slavery, he certainly didn’t discover in the West an antiracism that passes muster today. He wrote open-mindedly in Roughing It about the West Coast’s growing number of Chinese immigrants, moralizing against “the scum of the population,” including “policemen and politicians,” who abused them — but the book abounds in slurs and stereotypes, and a section maligning the Goshute people of Nevada and Utah stands out as especially hideous. (Notably, the tin-eared Harte failed even more miserably on these counts; in his most popular work, the poem “Plain Language from Truthful James,” he attempted to satirize anti-Chinese racism but instead produced a horrible bit of minstrelsy that delighted bigoted audiences who didn’t get the joke.)

Roughing It is often celebrated as having punctured some of the country’s most treasured myths about its Western frontier — even as an “autopsy of the American Dream,” as Twain scholar Hamlin Hill put it. “Having left home for the first time to seek romance, freedom, success, wealth and fame in the West,” Hill wrote, “the narrator finds instead cold-blooded murderers, rigged juries, paper speculation in stocks, and blighted hopes, including his own.” Undoubtedly, Clemens’ experiences in Nevada, chronicled in Roughing It’s hilarious middle chapters on the iniquities and absurdities of the silver boom, helped awaken him to the Gilded Age venality that he would spend much of the rest of his career assailing. In the book’s final paragraph — helpfully labeled “MORAL.” — he offers readers some simple advice: “Stay at home and make your way by faithful diligence.”

But even as Mark Twain ridiculed the get-rick-quick delusions of prospectors and speculators across the West, Sam Clemens found himself permanently afflicted with the fortune-seeking impulse that he first felt combing the hillsides outside Virginia City for specks of silver. Quite apart from any literary ambition, he harbored a lifelong desire to join the ranks of the country’s burgeoning industrialist elite, leading to a series of ruinous investments in everything from railroad stocks and a publishing company to a newfangled typesetting machine and “Plasmon” protein powder, a kind of turn-of-the-century Soylent. He was saved from bankruptcy in the 1890s largely thanks to the interventions of his friend Henry Huttleston Rogers, a ruthless Wall Street monopolist who had helped John D. Rockefeller build Standard Oil. (“Hell Hound Rogers” leaned on Clemens, in turn, to ingratiate himself with literary figures like S.S. McClure and Ida Tarbell, managing to be the only robber baron portrayed relatively sympathetically in the latter’s muckraking history of Rockefeller’s company.)

It was all a far cry from what Twain had wished for in his lowest moments in Roughing It, when his hopes of striking it rich had been dashed and, recalling the simple, decent living he had made piloting riverboats, he “long[ed] to stand behind a wheel again and never roam any more.” Twenty years later, in the memoir Life on the Mississippi, the thought was still on his mind: “Time drifted smoothly and prosperously on, and I supposed — and hoped — that I was going to follow the river the rest of my days, and die at the wheel when my mission was ended. But by and by the war came.” After the war, the riverboats kept running — they’re still running today — but there was no going back to the way things were. Mark Twain may have exposed the frontier as a place that was lawless and unromantic, a place where a few winners got ahead of the rest only through dumb luck and brutal violence, but America and its most famous author turned out to like that place just fine.