Shell games

On the Populists, Soapy Smith and the changing face of the con

“My gang, Bob! I’m going to be the government! I’m going to run things around here!”

—Ron Hansen, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford

As a genre, the Western is hopelessly obsessed with the end of the historical era it mythologizes. It’s there in the earliest Wister and Remington stories, it’s there in the golden-age films that mourned the loss of the country’s frontier spirit, and it’s there in the darker, more honest meditations on what the Wild West really was. On some level, every American has wrestled with the question of when it was that the frontier finally closed, what it meant for a country so long defined by something to lose it, where all the cowboys had gone. For all this fixation, though, there’s little consensus on an actual endpoint. When, exactly, did the Old West die? Where do you draw the line? It is, of course, an impossible question to answer — inescapably reductive, deplorably anglocentric, of no practical value, ill-conceived from the start. Anyway, I think the Old West died on March 15, 1894.

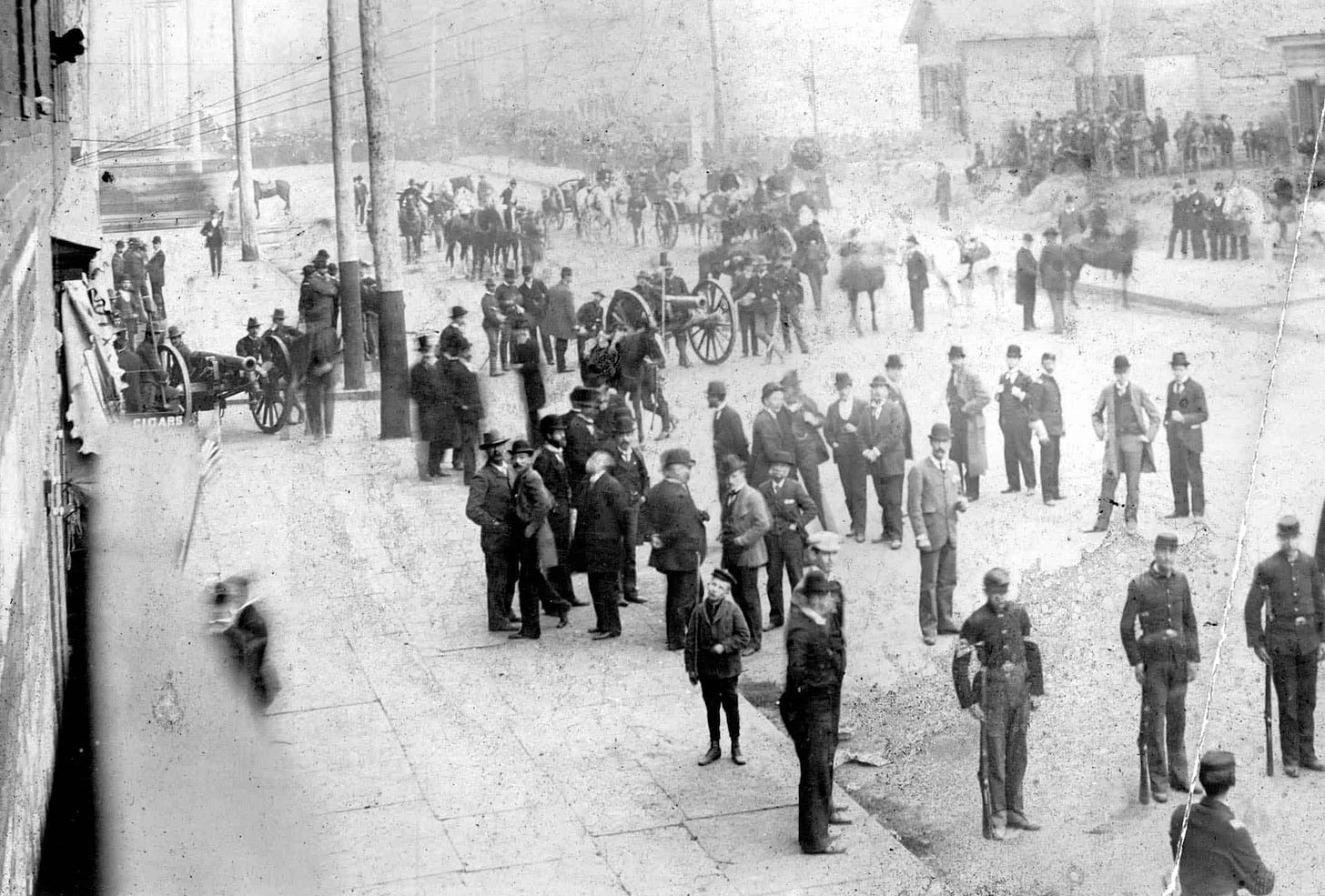

It happened in Denver, sometime in the late afternoon, while General T.J. Tarnsey of the Colorado National Guard sat on his horse a block from City Hall, awaiting orders to assault the building with a force of 300 men. It happened while con artist and gangster Jefferson “Soapy” Smith was lurking nearby, hidden among a large crowd of onlookers, waiting with a group of other gunmen loyal to City Hall to ambush Tarnsey and the militia from behind as soon as the fighting began. It happened while Edward Keating, then a young proofreader for the Denver Republican and later a three-term Colorado congressman, eyed both Smith and Tarnsey amid the commotion. “If trouble started,” he wrote in a 1964 memoir, “I hoped to have a front seat.”

Governor Davis Waite had called in the Guard amid a dispute over the Denver Fire and Police Board, whose members he had the power to appoint and dismiss. In its third decade of existence, Colorado’s capital had grown into a city of over 100,000 residents — and a notorious hive of corruption. Wealth flowed downstream into the city from the mining camps, and Gilded Age monopolies concentrated it the hands of the few: Eastern trusts gobbling up the railroads, mines, smelters and other industrial interests while a burgeoning local elite enriched themselves through lucrative utility franchises. The silver crisis and the Panic of 1893 only worsened inequality. The People’s Party, founded by a coalition of early labor activists and farmers’ organizations, swept to power in Colorado in 1892, and the unassuming Waite, an Aspen newspaper publisher and former school superintendent, became the first (and to date, only) third-party governor in state history.

Led by Waite, the Populists crusaded against Wall Street and the robber barons, but they also took aim at Denver’s criminal underworld, the gamblers and gunfighters who often served as strikebreakers and ballot-stuffers for the monopolists’ political machines. Organized crime “usually worked in alliance with the banks, utilities and special interests, i.e., the forces which more or less ran Denver as their own bailiwick,” writes local historian Phil Goodstein in Denver from the Bottom Up: From Sand Creek to Ludlow. “By checking gambling and assuring an honest police force, Waite believed, the Populists would be a step closer to achieving their goals.”

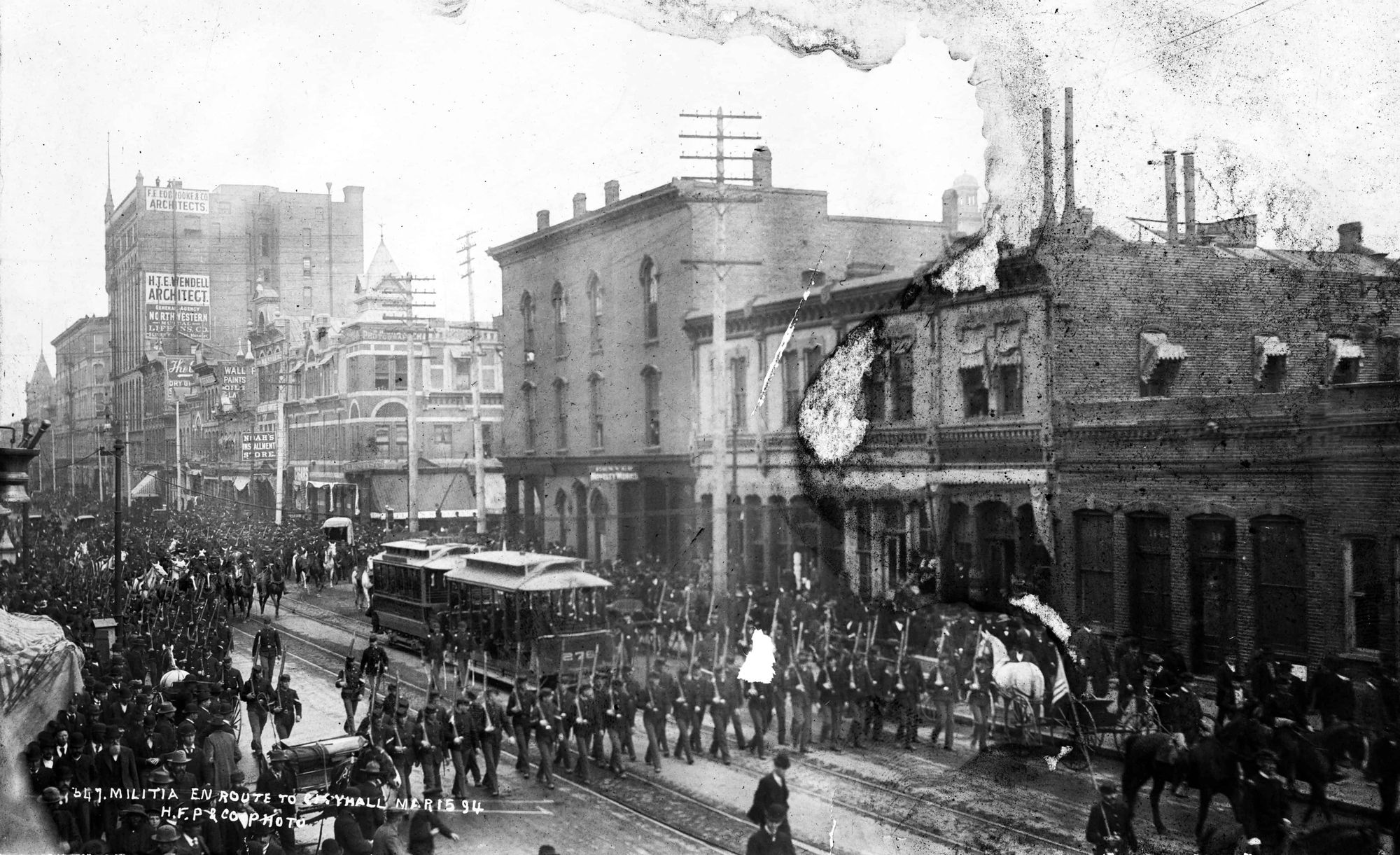

In early 1894, when two of his appointees to the Fire and Police Board proved just as corrupt as their predecessors, Waite fired them. They refused to go, and the ensuing standoff escalated quickly. The governor called in the National Guard, preparing to remove the two commissioners by force if necessary; Denver police were ordered to barricade City Hall, then located at 14th and Larimer Streets. Five companies of guardsmen marched into Denver, took up positions on the other side of Cherry Creek and trained cannons and Gatling guns on the building; city officials and their allies, including some of Denver’s most powerful gangsters, stockpiled dynamite and enough supplies to survive a weeks-long siege. Waite commissioned loyal Populists as state game wardens, enabling them to carry guns; police armed and deputized hundreds of outlaws.

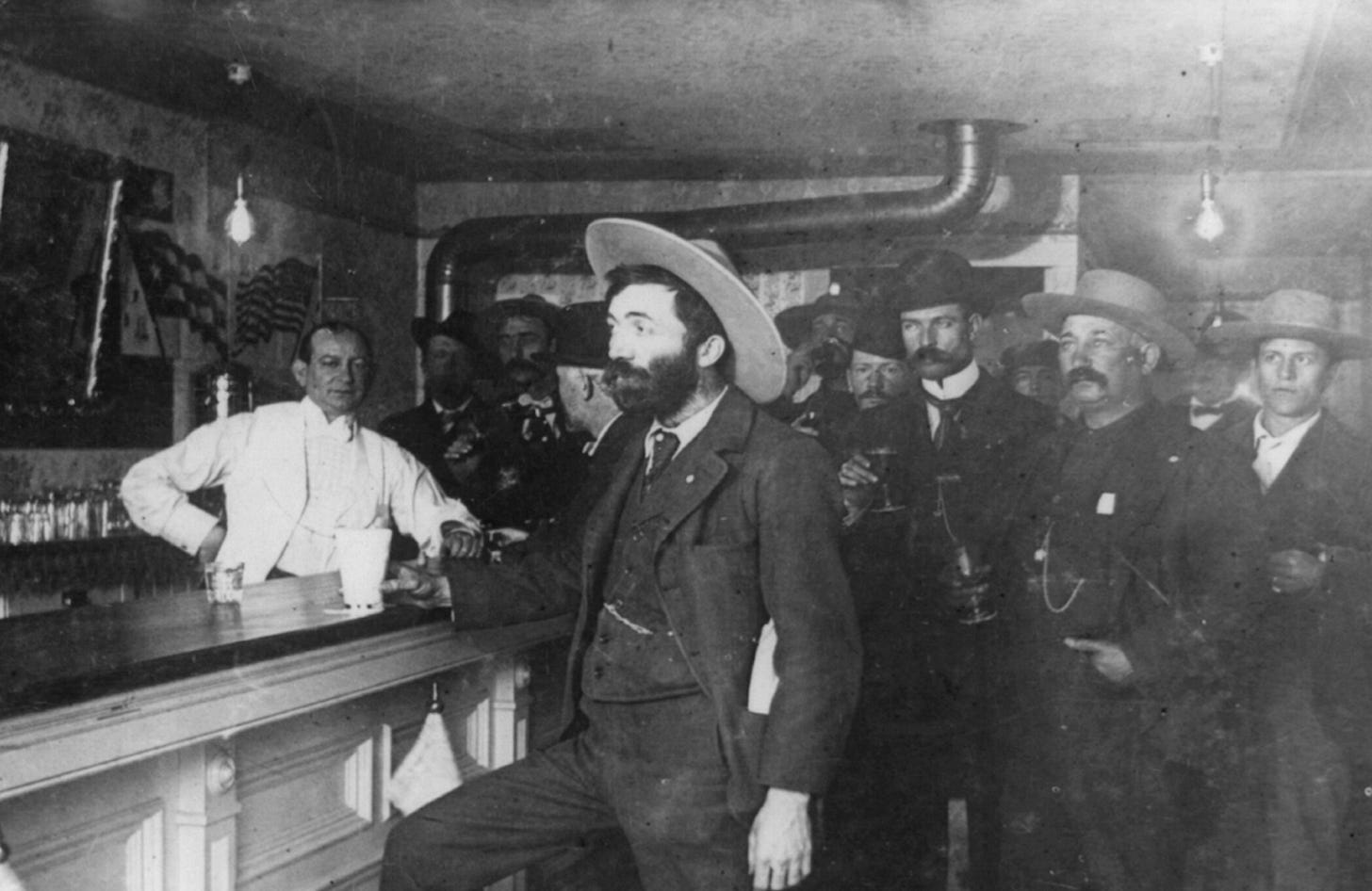

Soapy Smith had gotten his name from one of his signature cons, a modified shell game in which he slipped a $100 bill into a packaged bar of soap, inviting onlookers to try to pick it out from a pile of others for $5 a pop. (The swindle lives on as a gag gift and, bafflingly, a viral TikTok craze.) Now, in his final days in Denver, as years of conflict over vice and petty corruption culminated in what would become known as the City Hall War, Soapy, serial fraudster and underworld kingpin, briefly got another name: Colonel Smith of the Arapahoe County Sheriff’s Office.

Tarnsey waited for his orders. Smith waited to gun the general down. Keating and thousands of others watched. Federal troops were marching up from Fort Logan, or maybe they weren’t. Denver, frontier town on modernity’s doorstep, waited to see if blood would flow in its streets, along the tracks of its cable cars, lit by its electric department-store billboards — an American city turned war zone, two armies full of crooked cops and card sharps and radicalized homesteaders and newspapermen in a raw struggle for power. The standoff lasted into the evening. A single shot — a false move or a loss of nerve by any one of the hundreds of gunmen facing off at 14th and Larimer — could have lit the powder keg.

Nothing happened. All day long, a few well-dressed businessmen had been shuttling back and forth between City Hall and the governor’s apartments a few blocks away. They were Chamber of Commerce men, led by Rocky Mountain News founder and Denver gray eminence William Byers, and they pleaded with Waite to stand down. At last, the governor, having been assured that the Colorado Supreme Court would settle the issue without delay, agreed, and then and there, in a private office in the Equitable Building — in a thousand other such rooms before and after, during a century or three of conquest and compromise and the careful consolidation of power — whatever was Wild about the West was tamed.

For much of his life, Soapy Smith was always late to the action, one step behind fame and fortune. Born to a Southern planting family soon ruined by the end of slavery, he drove cattle on the Chisholm Trail in the late 1870s, well after the heyday of the true vaqueros and just before the railroads and barbed-wire ranches closed the trails for good. Wandering west, he arrived in the silver boomtowns of the Colorado Rockies only after the lucky few had struck it rich. There was little else for Smith to do, really, but prey on his fellow latecomers with shell games and other small-time rackets, and for much of his career as a confidence man he flitted between Denver and the mining camps, ditching one for the other when his schemes drew too much heat.

A lightly fictionalized Smith appears in the final chapter of Ron Hansen’s The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, a menacing rival to Ford in the months before his death in Creede in 1892. Swiftly taking over the town’s saloon and gambling business, with his easy outlaw charisma he haunts Ford as an apparition from his past, “a reincarnation of Jesse James, Jesse James, Jesse James.” Hansen’s account is rooted in fact, but the comparison is only half true. Soapy Smith was a swindler, not a bona fide Western badman. “Jeff was never an outlaw in the Jesse James or Dalton tradition,” wrote Frank G. Robertson and Beth Kay Harris in an entirely too sympathetic 1961 biography, Soapy Smith: King of the Frontier Con Men. “Those were men of direct action, primitive in their thoughts and depending on their guns. Jeff Smith came to live by his wits, and his gun was never more than a reserve accessory.”

Why rob a train in the dark of night when you can stand outside Union Station in broad daylight, cheating new arrivals out of their money with a bit of showmanship and a few bars of soap? Smith was an evolution of Jesse James, not a reincarnation. The Western highwayman and the bunco-steerer overlapped, they collaborated, one blended into the other, but as the map filled in — as the settlers and the telegraph lines and the bright lights of the cities left fewer places for bandits to hide — there was never any doubt about which one was better adapted for survival.

As his profile rose in Denver in the 1880s, Smith made friends with the police, greased the palms of the city’s elite, offered his gang’s services to the state’s powerful Republican political establishment. In his short reign in Creede, Colorado’s last silver boomtown, he did one better: “Calling a group of leading citizens and businessmen together,” wrote Robertson and Harris, “he set about getting some sort of government.” In Hansen’s telling, “Soapy appointed himself as president of a Gambler’s Trust… He manipulated people and preferences to such a degree that within weeks his good friends were made mayor, city councilmen, coroner, and justice of the peace.”

Unfortunately for Smith, the world kept changing, and there were only so many ungoverned mining camps left for his gang to take over. All over the West, the maps were filling in, the lights getting brighter, and the thin veneer of legitimacy he’d achieved as a boss of the Denver underworld was no longer enough. The City Hall War ended bloodlessly and inconclusively, but it marked a turning point; Governor Waite got his way at the Supreme Court, and Denver’s brush with civil war shocked its ruling class into action. “A genuine reform wave set in,” Robertson and Harris wrote, “and it became apparent to Soapy that his days in Denver were numbered.” Smith chased the frontier all the way to Skagway, Alaska, where he built a similar empire before he was killed in a shootout in 1898.

And so, sure, the fading away of such a neatly liminal figure, cowboy turned proto-mobster, feels as fitting an event as any to mark the end of what we think of as the Old West. But like the Jesse Jameses before them, the Soapy Smiths of the world didn’t so much as go extinct as learn to evolve. As the world got smaller, Smith found that his schemes were a few degrees beyond what polite society would tolerate any longer. He got ran out of town, but the industrialists and party bosses whose machines his gang had provided the muscle for stuck around, and today there are statues and plaques and street signs bearing their names all over Denver. Why run a shell game to fleece passengers at a streetcar stop when you could own stock in the tramway monopoly, and fleece them at the farebox and in the assessor’s office?

If the West had once been a place of unbounded possibilities, of sudden and violent swings in power and fortune, of freebooters and fanatics and falling empires, slowly it became something else, a place like any other — a place where power simply accrues, where the structures governing it ossify. Bit by bit, the violence got a little less capricious, a little more orderly. The cons got a little less obvious, a little more sophisticated — systematized, legitimate, smiling. If it wasn’t always progress, at least it always looked like it.

Even in the blood-and-thunder days of Spanish conquest, forward-thinking imperialists like the explorer Alejandro Malaspina envisioned a day when the West could be rid of the “frightening noise of the cannon and war, replacing them with the sweet ties of lucrative trade.” In Las Vegas, the mafia ran the casino business at gunpoint right up until the billionaires and corporations took it over. Today in Colorado you can gamble on your smartphone. “Don't get the idea I'm one of those goddamn radicals,” Al Capone told the British journalist Claud Cockburn in 1930. “Don't get the idea I'm knocking the American system. My rackets are run on strictly American lines.”

Davis Waite, who served only one two-year term as governor, was a radical, capable of summoning a biblical fury when denouncing the moneyed interests that he believed were immiserating the West and its people. From Denver’s monopolist-owned newspapers he earned the nickname “Bloody Bridles” Waite, for an 1893 anti-Wall Street speech in which he declared: “It is better, infinitely better, that blood should flow to the horses’ bridles, rather than our national liberties should be destroyed.” It was, quite literally, an apocalyptic vision, and it echoed one of the country’s founding mottos. Rarely, though, do we actually have to choose; there will always, it seems, be a few well-dressed businesspeople in an office somewhere, working quietly to give us a different set of options. In the history of the West, as in the history of most other places, we find no final reckonings.

That’s different, of course, than saying that history only flows in one direction, or that anything about the future is guaranteed. The two cannons that were aimed at Denver City Hall in 1894 belonged to a company known as the Chaffee Light Artillery, and in 1909 they were decommissioned and installed as part of a Civil War monument just below the steps of the Colorado State Capitol. They sat there, pointed across Civic Center Park in the direction of the City and County Building, for 111 years, until a crowd of antiracist demonstrators toppled the monument’s statue last summer. The next day, the cannons were hauled away on a flatbed truck by city officials, and they’re still missing.